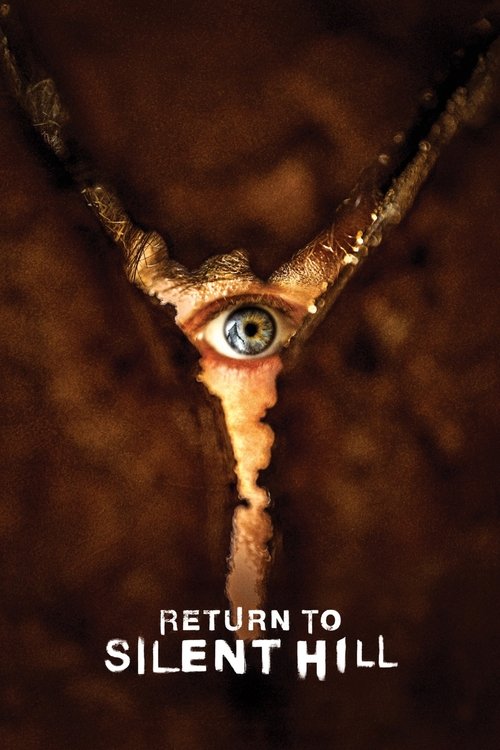

The Geometry of GriefIn 2006, Christophe Gans did something largely unprecedented: he made a video game adaptation that felt like cinema. It was flawed, certainly, but it possessed a texture—a rusty, industrial grandeur—that understood the source material was not about jump scares, but about place. Now, twenty years later, Gans returns to the fog with *Return to Silent Hill*. Arriving two decades after his first foray, this film attempts to scale the Mount Everest of survival horror narratives: the story of James Sunderland and his dead wife, Mary. The result is a film that is visually suffocating, emotionally operatic, and frustratingly polished.

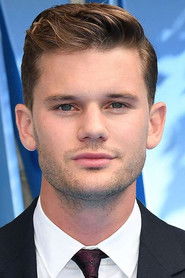

Gans has always been a director of tableaux rather than kinetics. In *Return to Silent Hill*, he treats the titular town less like a geography and more like a purgatorial stage play. The film opens not with a scream, but with the quiet, crushing banality of a letter. James (Jeremy Irvine) receives word from his wife, dead for years, inviting him to their "special place." From the moment James steps out of his car and into the unnatural mist, Gans imposes a dream logic that feels closer to Cocteau than Capcom. The town is bathed in a spectral, blue-grey light that feels cold to the touch. It is a beautiful nightmare, though one might argue it is *too* beautiful; the grime and rot of the game’s aesthetic have been aestheticized into something almost baroque.

The film’s greatest strength, and perhaps its most divisive element, is its refusal to behave like a modern horror film. There are few "stings" or rapid edits. Instead, the camera drifts. The horror here is practical and physical. Gans has famously utilized dancers and acrobats to portray the town’s monstrosities, and the effect is unnerving. The faceless nurses do not just stumble; they convulse in a synchronized ballet of pain.

However, the weight of the film rests entirely on Jeremy Irvine’s shoulders, and it is a heavy burden. James is a character defined by repression—he is a void where a man used to be. Irvine plays him with a hollowed-out fragility that works in the quiet moments, though he sometimes struggles to project the internal violence required for the third act. The "Orpheus" myth is the explicit text here; James is descending into the underworld not just to find his wife, but to be punished for the audacity of his survival.

The central discourse surrounding this film will undoubtedly focus on the inclusion of Pyramid Head. In Gans’ 2006 film, the monster was a terrifying, if misplaced, mascot. Here, the creature is finally restored to its proper context: an executioner manifesting from James's own guilt. The scenes involving this geometric titan are filmed with a reverence that borders on religious. When the Great Knife drags across the floor, the sound design—anchored by Akira Yamaoka’s legendary, discordant score—vibrates in the sternum. It is in these moments that the film transcends its genre trappings and becomes a study in masochism.

Yet, the film falters in its pacing. The narrative beats of the investigation sometimes feel like a checklist of locations rather than a fluid journey. The transition from the "fog world" to the "otherworld" lacks the visceral shock of the 2006 original, feeling more like a digital cross-fade than a tearing of reality.

Ultimately, *Return to Silent Hill* is a fascinating artifact. It rejects the cynical "universe building" of modern franchises in favor of a self-contained tragedy. It suggests that the scariest monsters are not the ones with pyramids for heads, but the memories we refuse to bury. It is an imperfect film, occasionally stifled by its own reverence for the source material, but it respects its audience enough to demand they sit in the silence, rather than just waiting for the next scream.