✦ AI-generated review

The Art of Falling Apart

In the hierarchy of Hollywood mythology, the stunt performer occupies a strange, spectral tier: they are the body without a face, the kinetic force behind the static image of stardom. They bleed so the poster boy remains pristine. David Leitch’s *The Fall Guy* (2024) is ostensibly a blockbuster action-comedy adapted from a dusty 1980s TV series, but beneath its pyrotechnic surface, it operates as a surprisingly tender reclamation of this invisible labor. Leitch, a former stunt double for Brad Pitt turned A-list director, hasn't just made a movie about blowing things up; he has crafted a surprisingly soulful meditation on the professional necessity of taking a hit and the personal terror of getting back up.

The film’s visual language is a deliberate collision between the polished and the painful. Leitch, working with cinematographer Jonathan Sela, creates a world that feels tactile and bruised. Unlike the weightless, pixelated destruction of the modern superhero canon, the action here has mass. When Colt Seavers (Ryan Gosling) is thrown against a wall or dragged behind a truck, the camera lingers not just on the spectacle, but on the wince-inducing aftermath—the ice packs, the back braces, the shattered glass. The film’s centerpiece—a record-breaking cannon roll that flips a car eight and a half times on a sandy beach—is shot with a reverence usually reserved for religious iconography. It is a sequence that screams of practical danger, rejecting the safety of the green screen to remind us that cinema, at its root, is a physical medium.

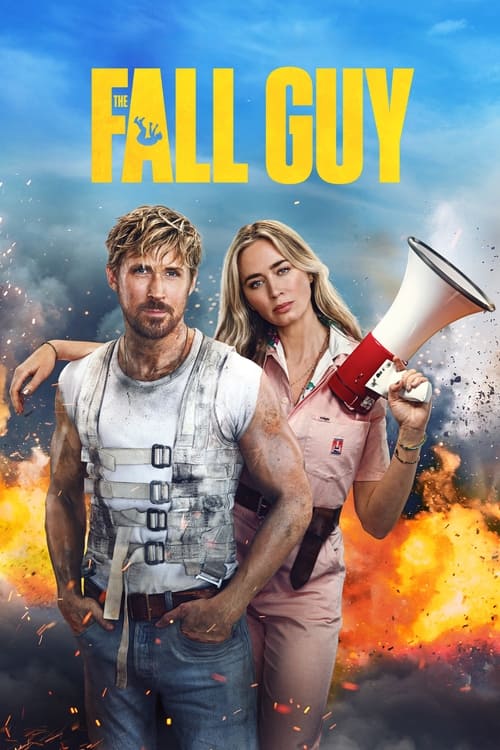

Yet, the film’s true success lies in how it intertwines this physical resilience with emotional vulnerability. The script cleverly uses the mechanics of filmmaking to deconstruct the romantic comedy. The narrative engine isn’t really the missing movie star (a hilariously vapid Aaron Taylor-Johnson) or the criminal conspiracy; it is the fractured relationship between Colt and director Jody Moreno (Emily Blunt).

There is perhaps no better metaphor for a breakup than the scene where Jody directs Colt to be set on fire repeatedly. As she barks direction through a megaphone, critiquing his performance while actually dissecting their failed relationship, Colt stands engulfed in flames, offering a literal thumbs-up while burning alive. It is a brilliant fusion of text and subtext: the stuntman’s job is to endure pain stoically, but the man inside the suit is incinerating. Gosling, who has perfected the art of subverting his own leading-man beauty, plays Colt not as an invincible super-soldier, but as a working-class artist whose body is his canvas. He cries to Taylor Swift in his truck; he panics; he fails.

Ultimately, *The Fall Guy* suffers slightly from the very maximalism it critiques—the third act bloats with narrative complications that distract from the human core. However, its spirit remains infectious. In an era where "content" is often generated by committees and rendered by servers, Leitch offers a reminder that the most thrilling special effect is still a human being risking gravity for the sake of a good shot. It is a film that asks us to look past the star on the poster and applaud the person hitting the ground.