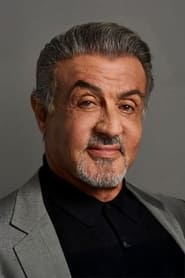

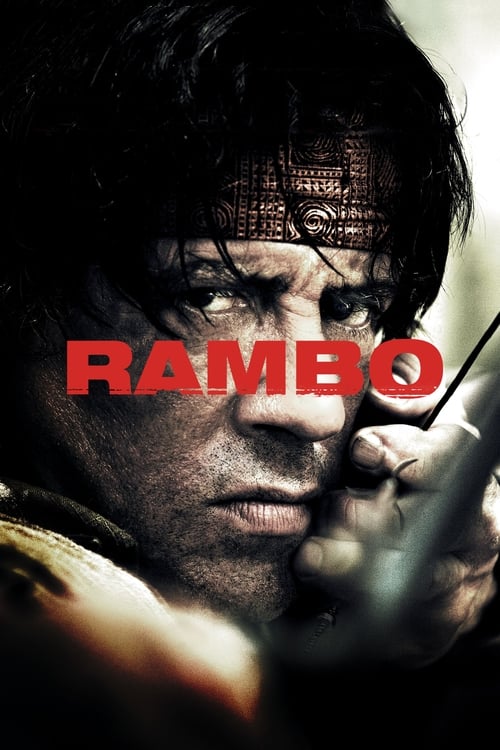

The Architecture of AtrocityCinema often treats the action hero as an immortal instrument of justice—a polished statue that deflects bullets and ages only in wisdom, never in weariness. But in 2008, Sylvester Stallone returned to the character that defined the jagged edge of 1980s American exceptionalism and did something startling: he stripped away the myth to reveal the butcher beneath. *Rambo* is not a nostalgia trip, nor is it a victory lap. It is a grim, nihilistic corrective to the cartoonish excesses of its predecessors, a film that posits war not as an adventure, but as a meat grinder that consumes the righteous and the wicked alike.

Stallone, serving as both director and star, abandons the slick, MTV-style editing of the action genre’s golden age. Instead, he adopts a visual language that is suffocatingly tactile. The film is drenched in mud, rain, and humidity; you can almost smell the rot of the jungle and the iron tang of blood. The cinematography does not glamorize the landscape of Thailand (standing in for Myanmar); it presents it as a purgatory where John Rambo has been waiting to die. When the violence inevitably erupts, it is not the clean, bloodless gunplay of a PG-13 blockbuster. It is industrial, gruesome, and confrontational. Stallone wants the audience to feel the weight of every bullet, transforming the action beat from a moment of excitement into a moment of revulsion.

The narrative engine is deceptively simple: Rambo is hired to ferry a group of idealistic Christian missionaries upriver into war-torn Burma. The missionaries, armed with faith and medical supplies, represent a naive morality that Rambo abandoned long ago. The friction between their hope and his despair forms the film's philosophical core. When Rambo warns them, "Go home... you're not changing anything," he isn't being cynical; he is speaking from a place of absolute, traumatic clarity. The film’s portrayal of the Burmese military junta is harrowing, grounding the movie in a specific, horrifying geopolitical reality that most action films would dare not touch. By placing a fictional 80s icon into the very real context of the Karen conflict, Stallone creates a jarring, effective dissonance.

What elevates *Rambo* above a standard exercise in exploitation is Stallone’s performance. Stripped of the dialogue-heavy bravado of the past, he communicates almost entirely through a physicality that screams exhaustion. He moves like a man carrying the ghosts of every person he has ever killed. The climax, a cacophony of .50 caliber destruction, serves as a dark catharsis—not a triumph of good over evil, but an acceptance of a terrible nature. Rambo fights not because he believes in the cause, but because, as he admits, "war is in his blood." It is a tragic admission of a soul permanently shaped by violence.

In the final shot, as Rambo walks down a dusty American road, finally returning home, the film achieves a quiet poignancy. It suggests that the only way to end the war is to walk away from it, yet the previous ninety minutes have proven that the war never truly leaves the warrior. *Rambo* (2008) remains a brutal, essential entry in the canon of war cinema—an ugly film about an ugly world, directed with an uncompromising, ferocious honesty.