✦ AI-generated review

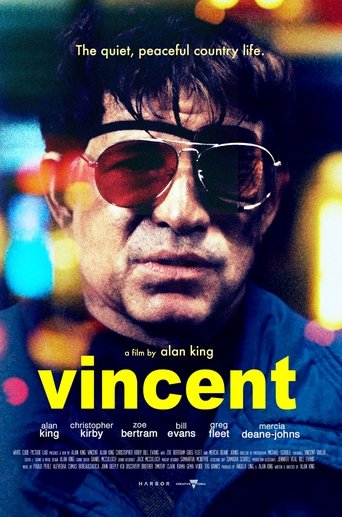

The Theology of the Fist

South Korean cinema has spent the last decade perfecting the art of the occult. From the weeping dread of *The Wailing* to the shamanistic precision of *Exhuma*, these films usually treat the spiritual world as a terrifying, unknowable abyss where human fragility is exposed. But *Holy Night: Demon Hunters* (2025) asks a blunt, almost heretical question: What if you could just punch the abyss in the face?

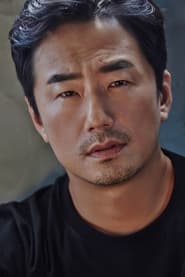

Directed by Lim Dae-hee in his feature debut, *Holy Night* is less a horror film and more a kinetic collision of genres. It operates on the premise that evil is not just a spiritual corruption but a physical nuisance that requires removal. At the center of this philosophy is Ba-woo, played by the indomitable Don Lee (Ma Dong-seok). Lee has spent years curating a specific cinematic persona—the "unbothered tank"—and here, he transposes that energy into a realm usually reserved for crucifixes and holy water. The film’s cultural proposition is fascinating: it suggests that in an era of complex, intangible anxieties, we collectively crave a solution as simple and tangible as a sledgehammer.

Visually, Lim struggles to marry two disparate aesthetics. The film oscillates between the smoky, claustrophobic lighting of a traditional exorcism thriller and the wide, dynamic framing of a superhero brawl. There are moments where this friction sparks brilliance. In one standout sequence, the camera tracks Ba-woo wading through a hallway of possessed cultists. The sound design is crucial here; instead of the squelching gore typical of zombies, the impacts sound like thunderclaps, grounding the supernatural threat in heavy, undeniable reality. However, the film often loses the "horror" in this equation. It is difficult to feel dread when the protagonist treats a demonic entity with the same casual annoyance one might have for a parking ticket.

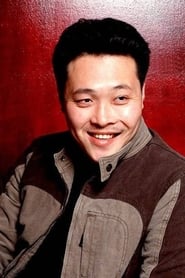

Despite the spectacle, the film’s emotional anchor—and perhaps its missed opportunity—lies in the victim, Eun-seo (played with terrifying commitment by Jung Ji-so). The possession genre relies on the violation of the self, the tragedy of a person displaced from their own body. Jung’s contortions and shifts in voice provide the film’s only true glimpses of the uncanny. Yet, the narrative, seemingly impatient to get back to the punching, often sidelines her internal struggle for the external rescue mission. The "Holy Night" team, including the shamanistic Sharon (Seohyun) and the tech-savvy mood-maker Kim Gun (David Lee), function efficiently, but they feel like RPG party members filling stat slots rather than fully realized human beings grappling with the divine.

The climax, which hints at Ba-woo using the demon’s own power against it, teases a more complex relationship with evil—suggesting that to fight monsters, one must invite them in. But the film retreats from this psychological precipice, preferring the safety of a decisive knockout.

*Holy Night: Demon Hunters* ultimately serves as a fascinating artifact of modern blockbuster fatigue. It rejects the slow-burn ambiguity of high-concept horror in favor of catharsis. It is not a film that haunts you; it is a film that assures you that even the devil has a glass jaw. While it lacks the spiritual depth of its genre peers, it offers a peculiar, muscular comfort: the fantasy that no matter how dark the night gets, it can be beaten into submission.