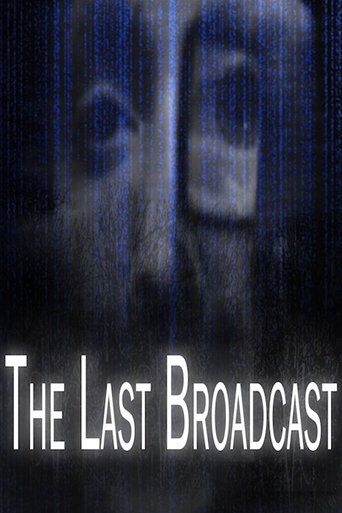

✦ AI-generated review

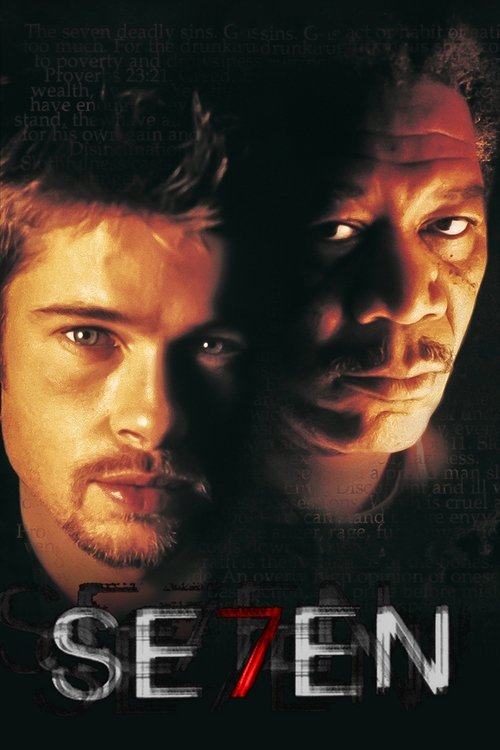

The Theology of Rot

The rain in David Fincher’s *Se7en* (1995) does not cleanse; it erodes. It falls relentlessly on an unnamed, decaying metropolis, turning the streets into a slick, reflective purgatory where the sun seems to have been permanently extinguished. This is not merely a weather effect, nor is it a simple noir trope. In Fincher’s hands, the downpour is a moral texture—a physical manifestation of a world so saturated with sin that it has begun to liquify. Coming off the studio-mangled wreckage of *Alien 3*, Fincher didn’t just direct a thriller; he constructed a cathedral of dread, transforming a standard police procedural into a meditation on the inevitability of evil.

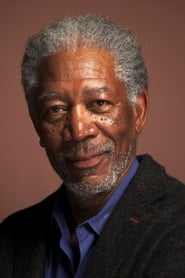

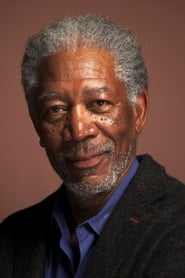

Visually, the film is a masterwork of oppression. Cinematographer Darius Khondji utilized a bleach-bypass process that deepened the blacks and desaturated the colors, creating a palette that feels bruised and gangrenous. The camera often lurks in the shadows, much like the film’s antagonist, forcing the audience to squint through the gloom alongside Detectives Somerset (Morgan Freeman) and Mills (Brad Pitt). When light does appear, it is intrusive and harsh—flashlight beams cutting through dust motes in a sloth-victim’s apartment, or the sterile fluorescence of a library where Somerset retreats to find order in Dante and Milton. Fincher uses these visuals to suffocate the viewer, denying us the comfort of clarity until the final, blindingly bright act.

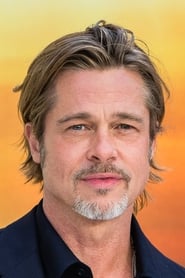

At its heart, *Se7en* is a collision between two tragic worldviews. Morgan Freeman’s Somerset is a man who has looked into the abyss and decided to quietly retire, his metronome ticking away the seconds until he can escape a city he believes is beyond saving. He is the film’s weary intellect, treating the horrific crime scenes with the detached sorrow of a historian. Opposing him is Brad Pitt’s Mills, a bundle of kinetic, naive energy who believes that badge and gun are enough to hold back the dark. Mills views the case as a puzzle to be solved; Somerset views it as a sermon to be endured.

The terrifying genius of the film lies in the realization that the antagonist, John Doe, is not hiding. He is performing. The detectives are not hunting a man; they are unwilling participants in a morality play written by a psychopath. The narrative collapses the distance between the investigator and the criminal, culminating in the devastating finale in the desert. Here, Fincher rips away the protective shroud of rain and darkness, exposing the characters to an unforgiving, high-noon sunlight. The horror of "the box" is not just in its gore, which is famously left to the imagination, but in its perfect, mathematical cruelty. By forcing Mills to become the embodiment of Wrath, Doe proves that apathy (Somerset) and heroism (Mills) are equally useless against absolute conviction.

Ultimately, *Se7en* remains a cornerstone of modern cinema not because of its shocks, but because of its profound pessimism. It broke the unspoken contract of the genre: that the detective restores order. In Fincher’s city, catching the killer offers no salvation. The bad guy wins, not by escaping, but by completing his masterpiece, leaving the heroes—and the audience—to live in the wreckage he designed.