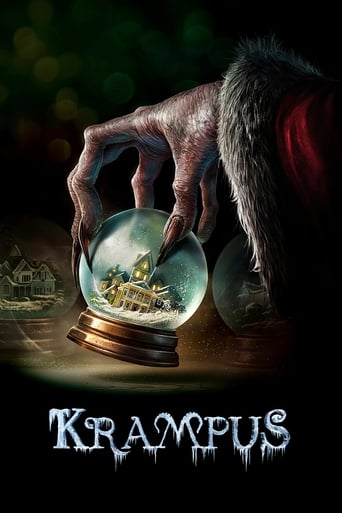

The Red Stain on the White SnowThe holiday film canon is typically a binary system: on one side, the saccharine Hallmark industrial complex, and on the other, the cynical anti-Christmas counter-programming. It is rare to find a film that attempts to occupy both spaces simultaneously, demanding we acknowledge the ancient, pagan bloodlust of the winter solstice while genuinely weeping for a saved child. Tommy Wirkola’s *Violent Night* (2022) is precisely that anomaly—a film that wields a sledgehammer with one hand and a candy cane with the other, creating a work that is as much a cultural exorcism as it is an action comedy.

Wirkola, a director who cut his teeth on the jagged edges of Nazi zombie horror (*Dead Snow*), brings a specific, tactile brutality to the proceedings. The visual language of *Violent Night* is defined by the collision of textures: the softness of velvet Santa suits and falling snow against the hardness of steel and bone. Wirkola understands that for the "Christmas magic" to feel earned in a cynical age, it must survive a trial by fire. The action choreography is not merely kinetic; it is thematic. When Santa, played with weary gravitas by David Harbour, engages in combat, it is not the weightless ballet of a Marvel film. It is heavy, exhausting, and messy. The film’s aesthetic leans into the grotesque to highlight the absurd—a "Home Alone" tribute sequence, for instance, strips away the cartoon physics of the 1990s to reveal the gruesome reality of what a booby trap actually does to a human body. It is a critique of our own nostalgia, asking us why we find violence funny only when it is bloodless.

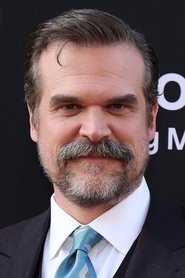

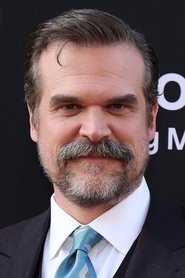

At the center of this carnage beats a surprisingly tender heart, largely due to David Harbour’s masterful performance. It would have been easy to play this Santa as a one-note drunkard, a *Bad Santa* riff with a body count. Instead, Harbour taps into a deep, mythical melancholy. His Santa is an ancient creature, a former Viking warrior ("Nicomund the Red") who has been domesticated by centuries of consumerism. He is not fighting to save the wealthy, morally bankrupt Lightstone family because he likes them; he is fighting to reclaim his own identity. The film posits that the modern "Santa" is a hollow shell, and only by reconnecting with his primal, warrior past can he protect the innocence of the one child, Trudy, who still believes. The violence, therefore, becomes a form of redemptive labor.

Ultimately, *Violent Night* succeeds where many genre mashups fail because it refuses to treat its premise purely as a joke. It commits fully to its own absurdity. By pitting the embodiment of generosity against the personification of greed (John Leguizamo’s "Scrooge"), the film constructs a fable about the struggle to maintain wonder in a world obsessed with material gain. It suggests that the "Christmas Spirit" is not a passive feeling of warmth, but an active, sometimes violent defense of light against the encroaching dark. In a cinematic landscape often afraid of sincerity, Wirkola delivers a film that bludgeons the viewer into believing again.