The Architecture of ChaosThere is a moment in *Beetlejuice Beetlejuice* where the digital sheen of modern Hollywood cracks, revealing something tactile, grotesque, and wonderfully handmade. It is not a scene of high drama, but a simple creature effect—a shrunken head or a sandworm—that moves with the jerky, stop-motion imperfection of a child’s nightmare. In an era where cinema is often smoothed into algorithmic perfection, director Tim Burton has returned to the messy, gothic sandbox of his youth. This is not merely a sequel; it is a reclamation of an aesthetic that views the afterlife not as a spiritual plane, but as a bureaucratic DMV waiting room run by the insane.

Burton’s visual language here is a defiant rejection of the green screen ubiquity that has plagued his recent output. Returning to Winter River thirty-six years after the Deetz family first encountered the bio-exorcist, the film feels less like a product of 2024 and more like a lost artifact from 1989. The director leans heavily into practical effects—animatronics that sputter, prosthetics that ooze, and sets that feel claustrophobic and painted. The "Soul Train" sequence, a literal funk-fueled locomotive to the Great Beyond, exemplifies this spirit. It is a visual pun brought to life with such feverish energy that it bypasses logic entirely to hit a nerve of pure, absurdist joy.

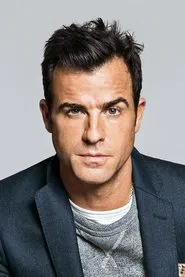

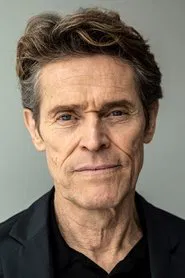

However, the film’s narrative architecture is as unstable as the Maitland’s original house. The script struggles under the weight of its own population. We are introduced to Astrid (Jenna Ortega), Lydia’s estranged daughter, who serves as the skeptical anchor to the supernatural madness. Ortega is excellent, channeling the sullen intelligence of Winona Ryder’s original performance while carving out her own space. Yet, the film is overcrowded with subplots: a soul-sucking ex-wife (Monica Bellucci), a ghost detective (Willem Dafoe), and a predatory suitor (Justin Theroux). These threads often tangle rather than weave together, creating a frenetic pace that sometimes mistakes noise for momentum.

Despite the narrative clutter, the emotional core remains surprisingly potent. At its heart, this is a film about the terrifying continuity of grief. Lydia Deetz (Ryder), once the ultimate outsider, is now a frantic mother terrified of losing her connection to the living, having spent a lifetime communing with the dead. The friction between Lydia, her stepmother Delia (the magnificent Catherine O’Hara), and Astrid grounds the supernatural hijinks in a recognizable human reality. O’Hara, in particular, remains a comic force of nature, turning grief into a piece of avant-garde performance art that is both hilarious and strangely touching.

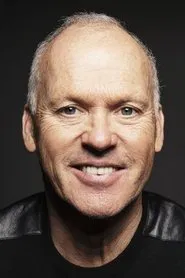

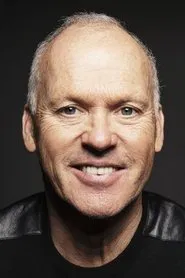

Michael Keaton, slipping back into the stripes of Betelgeuse, offers a performance that defies the passage of time. He is id personified—a rotting, lecherous trickster who has learned nothing and forgotten nothing. His presence is the film’s battery, charging every scene he inhabits with a dangerous unpredictability.

Ultimately, *Beetlejuice Beetlejuice* succeeds not because it is a perfect film, but because it is an honest one. It admits that nostalgia is a trap, even as it gleefully steps into it. It suggests that death is messy, life is absurd, and the only way to survive either is to embrace the chaos. In a cinematic landscape often sanitized of all texture, Burton has given us a film that dares to be ugly, weird, and alive.