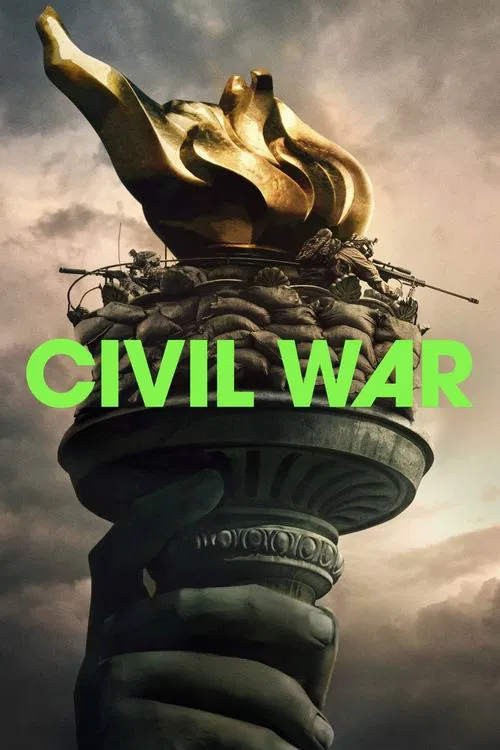

The Shutter Click as GunshotCivil war, in the popular American imagination, is often romanticized as a clash of ideologies—blue coats against gray, brother against brother for a defined cause. Alex Garland’s *Civil War* strips this conflict of its romance and, daringly, of its ideology. It presents a nation devouring itself not for a manifesto, but out of a mechanical, terrifying inertia. Garland, a filmmaker whose career has been defined by the high-concept cerebral sci-fi of *Ex Machina* and *Annihilation*, here pivots to a road movie that feels less like a warning and more like an autopsy of a body that hasn't quite finished dying.

The film’s visual language is its most potent weapon. Garland and cinematographer Rob Hardy eschew the shaky-cam chaos typical of modern war films for a composed, almost clinical stillness. The violence is loud, abrupt, and hideously matter-of-fact. When a sniper duel unfolds at a winter wonderland theme park, there is no swelling score to dictate how we should feel—only the dry crack of rifle fire and the surreal juxtaposition of plastic reindeer and blood. This dissonance creates a suffocating reality where the familiar geography of American commerce—strip malls, gas stations, highways—becomes a necropolis.

At the center of this collapse is Lee (Kirsten Dunst), a renowned war photographer whose face is a roadmap of every atrocity she has witnessed. Dunst delivers a performance of granite exhaustion; she is a woman who has hollowed herself out to become a perfect recording vessel. She is joined by Joel (Wagner Moura), an adrenaline-junkie writer, and Jessie (Cailee Spaeny), a young aspirant who views war photography with a naive, artistic ambition. The film functions as a grim mentorship, a transfer of trauma from one generation to the next. The tragedy is not just that Lee dies, but that Jessie learns to live by the same cold logic—that the image matters more than the human life within the frame.

The film’s most discussed sequence involves an unnamed soldier played by Jesse Plemons. In a few terrifying minutes, Plemons dismantles the film's "neutral" stance. Wearing red plastic sunglasses that make him look like a grotesque distinct from the green of the grass, he asks the journalists, "What kind of American are you?" It is a moment of pure, distilled xenophobia that anchors the film’s vague politics in a very specific, recognizable terror. Here, the lack of exposition regarding the war's origins ceases to matter. The gun in his hand is the only policy that counts.

Critics have argued that Garland’s refusal to map the film’s factions onto current Democratic or Republican divides is a cop-out. I argue it is a precise artistic choice. By blurring the lines—allying Texas with California, keeping the President’s ideology vague—Garland forces us to look at the violence itself rather than rooting for a "team." If we knew who the "good guys" were, we would forgive their atrocities. By denying us that comfort, *Civil War* forces us to confront the sheer, nihilistic waste of the conflict.

Ultimately, *Civil War* is a film about the cost of witnessing. It asks if the act of observing atrocities is a noble duty or a form of passive participation. In the film's final, heart-pounding raid on the White House, the camera shutter becomes indistinguishable from the gunshot. As the credits roll, we are left with a lingering, uncomfortable question: In a world consuming itself for spectacle, are we the mourners, or are we just the audience?