The Weight of SilenceThere is a particular kind of ghost that haunts the digital age—not a spirit in a white sheet, but a pixelated echo, a frozen frame of a loved one who is neither fully gone nor truly present. In *Shelby Oaks* (2025), director Chris Stuckmann, making the perilous leap from YouTube film critic to feature filmmaker, attempts to exorcise this specifically modern demon. The result is a film that wrestles with the architecture of belief, utilizing the very medium that made Stuckmann famous to deconstruct the obsession of looking.

Stuckmann’s journey to this film is well-documented—a record-breaking Kickstarter and the watchful eye of the internet’s commentariat—but *Shelby Oaks* demands to be judged not as a "creator’s" pivot, but as a piece of cinema. It largely succeeds, not because it reinvents the horror wheel, but because it understands that the most terrifying thing about a missing person case isn't the supernatural, but the suspension of grief.

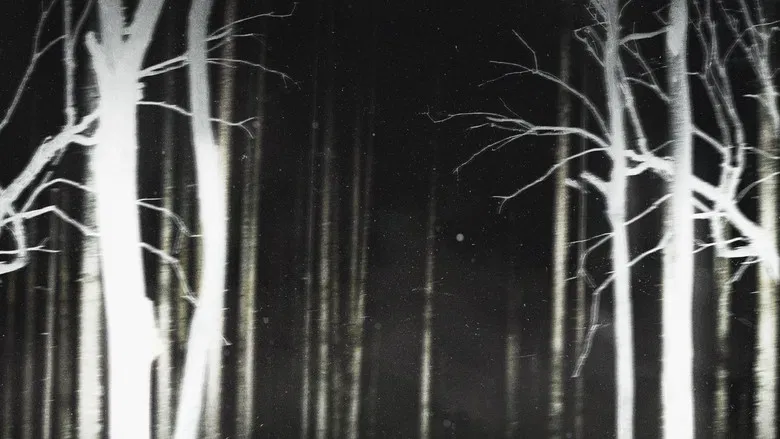

The film’s most daring structural gamble is its initial shapeshifting. We begin in the vernacular of the "Paranormal Paranoids," a fictional YouTube troupe whose disappearance twelve years prior has become internet folklore. Stuckmann captures the grainy, chaotic energy of early 2000s found footage with forensic precision—the digital artifacts, the shaky handheld panic, the naivety of youth facing ancient darkness. But just as we settle into this mockumentary rhythm, the film breaks its own rules, dissolving into a traditional narrative following Mia (Camille Sullivan).

This transition is jarring, perhaps intentionally so. It mirrors Mia’s own internal state: the cold, objective documentation of her sister Riley’s disappearance giving way to the subjective, suffocating reality of her present trauma. Visually, the film trades the claustrophobia of the lens for the vast, gray emptiness of Ohio (an often neglected backdrop in American horror). The atmosphere is heavy with damp earth and decaying industrialism, a visual language that suggests the town of Shelby Oaks is not just hiding secrets, but metabolizing them.

At the center of this atmospheric dread is Camille Sullivan’s Mia, a performance of raw, exposed nerves. Sullivan avoids the tropes of the "final girl" or the "intrepid investigator." Instead, she plays Mia as a woman hollowed out by ambiguity. Her search for Riley is not driven by hope, but by a desperate need to close a parenthesis that has been left open for a decade. The horror here is domestic and intimate; the supernatural elements—the whispers of the demon Tario, the cult-like devotion of the antagonists—are merely external manifestations of Mia’s internal rot.

Stuckmann’s direction shines brightest when he allows silence to speak. In a genre often reliant on jump scares (or "loud noises," as critics often lament), *Shelby Oaks* is remarkably patient. The dread accumulates in the corners of the frame. A scene involving a simple conversation in a diner feels as fraught as a séance, underscoring the film’s thesis: that trauma makes everything, even the mundane, feel like a threat.

Ultimately, *Shelby Oaks* is a tragedy masquerading as a mystery. It posits that some doors, once opened, cannot be closed, and that the search for answers can be more destructive than the mystery itself. While the third act stumbles slightly under the weight of its own mythology—leaning perhaps too heavily into explanation where ambiguity might have stung more—the emotional core remains intact.

This is a debut that proves the critic’s eye can indeed translate to the director’s chair. It is a film not about the monsters we film, but the monsters we become when we refuse to stop watching. Stuckmann has crafted a somber, thoughtful entry into the canon of American folk horror, one that lingers like the static on an old VHS tape after the movie has ended.