The Tuxedo as ArmorThe spy genre has always been a fantasy of competence. From Bond to Bourne, we watch these men not because they are relatable, but because they are efficient; they move through a chaotic world with the smooth precision of a Swiss watch. *Archer*, Adam Reed’s animated opus which concluded its fourteen-year run in late 2023, begins by asking a simple, devastating question: What if that competence was merely a side effect of profound emotional damage? For over a decade, this series masqueraded as a raunchy spoof, but beneath its surface of shaken martinis and suppressed gunfire lay one of television’s most intricate studies of arrested development.

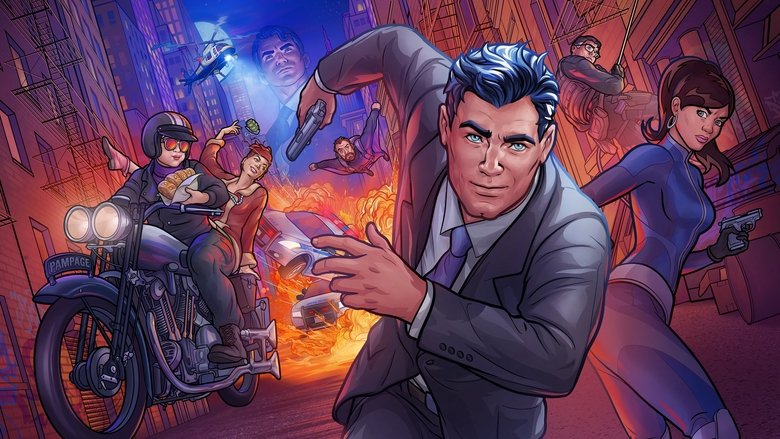

Visually, *Archer* established a language that was as rigid as it was beautiful. Drawing heavy inspiration from mid-century comic art—specifically the thick, bold lines of Jack Kirby and the pop-art polish of the 1960s—the show created a world that felt trapped in amber. The animation, particularly in early seasons, was intentionally limited; characters would often stand static, vibrating only with the energy of their rapid-fire, overlapping dialogue. This aesthetic choice was not merely budget-conscious; it was thematic. The world of ISIS (later "The Agency") was a beautiful, suffocating diorama where the furniture was mid-century modern, the technology was anachronistically digital, and the characters were locked in a cycle of abuse. The crispness of the art direction, with its heavy shadows and watercolor backgrounds, provided a stark contrast to the messy, screaming humanity of the people inhabiting the frame.

At the center of this stylish nightmare is Sterling Archer and his mother, Malory. While the series is famous for its genre-hopping—shifting from Cold War spycraft to *Miami Vice* drug running, and later into noir and sci-fi coma fantasies—the "heart" remained the Oedipal struggle between a son desperate for validation and a mother incapable of giving it. Sterling is not a hero; he is a weaponized id, a man who treats espionage like a playground because he never learned that actions have consequences. Yet, the brilliance of the series was how it slowly, painfully dismantled this invincibility.

The "Coma Seasons" (Seasons 8-10), often divisive among audiences, were actually crucial psychological excavations. They stripped away the spy veneer to reveal that Sterling’s subconscious was entirely populated by his coworkers, proving that this dysfunctional office was, tragically, the only family he had. The death of Jessica Walter (Malory) forced the narrative to finally confront the void Sterling had spent a lifetime trying to fill with alcohol and adrenaline. The finale, *Into the Cold*, didn’t just close the book on a comedy; it acknowledged that even the most stubborn man-child must eventually face the silence of an empty room.

Ultimately, *Archer* will be remembered not just for its "phrasing" jokes or its obscure literary references, but for its surprising endurance as a character drama. It deconstructed the myth of the cool spy by showing us the terrified boy inside the tuxedo. It argued that saving the world is easy; the hard part is sitting through a dinner with your mother without a drink in your hand. In a landscape of disposable animated comedies, *Archer* had the audacity to suggest that while trauma is tragedy, the way we survive it is often a farce.