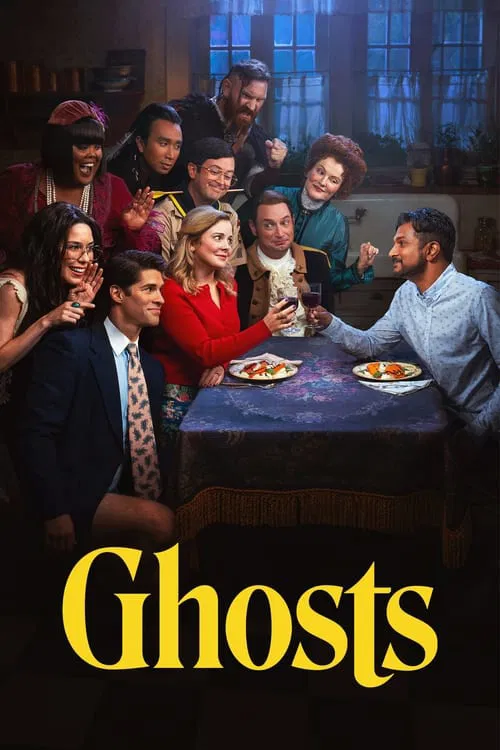

The Afterlife as a Found FamilyIn the landscape of modern television, where cynicism often masquerades as sophistication, the CBS sitcom *Ghosts* (2021) performs a quiet miracle: it makes the concept of purgatory feel like a warm hug. Adapted from the BBC series of the same name, this American iteration could easily have been a soulless clone—a "product" designed to fill a network time slot. Instead, it has blossomed into a distinct, humanistic exploration of history, connection, and the unfinished business of living. It is not merely a show about death; it is a show about the enduring, messy necessity of community.

The premise is deceptively simple. A young couple, Samantha (Rose McIver) and Jay (Utkarsh Ambudkar), inherit a crumbling country estate, Woodstone Manor. After a near-fatal fall, Samantha gains the ability to see the spirits who have died on the property over the last millennium. Visually, the show operates on a clever plane of dual reality. To Jay (and the rest of the living world), the manor is a quiet, drafty money-pit. To Samantha and the audience, it is a crowded, cacophonous stage filled with a motley crew of archetypes: a viking, a prohibition-era jazz singer, a closeted Revolutionary War officer, a hippie, and a pantless Wall Street bro, among others. The directors use this duality to brilliant comedic effect, often framing shots to emphasize the "empty" space Jay sees versus the chaotic tableau Samantha navigates.

However, the show’s true brilliance lies in how it subverts these archetypes. Take Trevor (Asher Grodman), the Wall Street financier who died in the year 2000. He spends eternity with no pants, a visual gag that initially signals he is a shallow, frat-boy caricature. Yet, in the standout episode "Trevor’s Pants," the script peels back the layers of this joke to reveal a surprising core of nobility. We learn he didn't lose his trousers in a debauched sexcapade, but gave them to a young associate being hazed, saving the boy from humiliation. It is a moment of profound empathy that recontextualizes a sight gag into a badge of honor. The show constantly invites us to look past the historical costume—the visual shorthand of "who they were"—to find the human soul beneath.

This emotional resonance is anchored by the performances, particularly Brandon Scott Jones as Isaac Higgintoot, the American revolutionary who is infinitely jealous of Alexander Hamilton. Isaac’s arc is a masterclass in slow-burn character development. His petty feuds and theatrical gasps mask a deep, centuries-old wound regarding his sexuality and his legacy. The show treats his eventual coming-out not as a "very special episode," but as a natural evolution of a man finally feeling safe enough to be himself—even if it took 250 years. The ghosts are stuck in a single location, but they are not stagnant; they are evolving through their friction with one another.

Ultimately, *Ghosts* argues that we are all, in some way, haunted—by our mistakes, our secrets, and the history we carry. But it also suggests that the cure for this haunting is not exorcism, but understanding. By forcing a diverse group of people from warring eras to share a living room, the series creates a microcosm of the American experiment itself: messy, loud, and often contentious, but bound together by the terrifying, beautiful fact that we are stuck with each other. It is a comedy that whispers a gentle truth: it is never too late to grow up, even if you’re already dead.