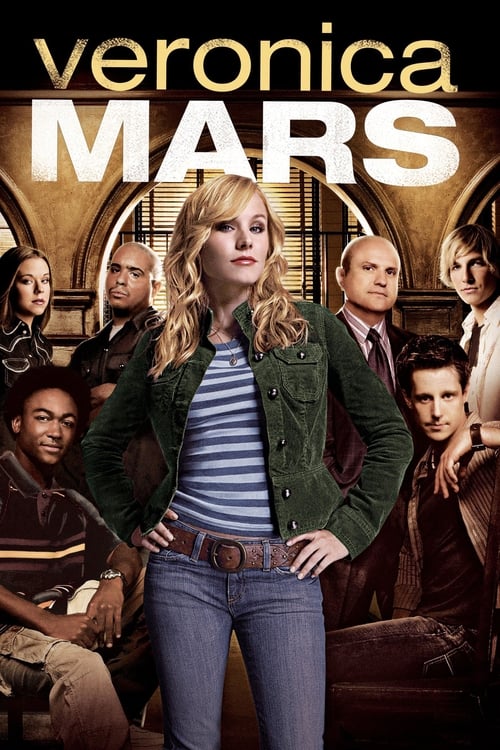

The Sunshine Noir of Neptune HighIf Raymond Chandler had been forced to attend pep rallies, or if Philip Marlowe had traded his fedora for a messenger bag, they might have recognized the soul of Veronica Mars. Premiering in 2004, Rob Thomas’s *Veronica Mars* arrived not as a typical teen soap, but as a hard-boiled detective novel disguised in the bright, saturation-dialed aesthetics of Southern California. It remains one of the most astute television texts of the early 2000s, a show that understood that high school is not just a social hierarchy—it is a brutal, microcosm of class warfare.

The series is set in the fictional town of Neptune, California, a place Veronica (played with razor-sharp cynicism by Kristen Bell) famously describes as "a town without a middle class." This is the show's thesis statement. While its contemporaries like *The O.C.* or *One Tree Hill* often glamorized wealth or treated poverty as a romantic obstacle, *Veronica Mars* treated economic disparity as a crime scene. The "09ers" (wealthy kids from the 90909 zip code) live in a completely different moral universe than the rest of the town. The visual language of the show emphasizes this divide: the sun is always shining in Neptune, but the lighting is often harsh, casting long, noir-ish shadows that cut across the characters' faces. It is "sunshine noir," where the brightness only serves to illuminate the rot more clearly.

At the center of this rot is Veronica herself. Kristen Bell’s performance is a high-wire act of vulnerability and calcified defenses. Following the murder of her best friend Lilly Kane and her own sexual assault—traumas the show handles with surprising gravity and lack of exploitation—Veronica retreats into the shell of the investigator. She uses her camera lens as a shield; if she is watching the world, the world cannot hurt her. The show’s use of voiceover, a classic noir trope, allows us access to her internal monologue, revealing a weariness that belies her age. She is an old soul in a young woman's body, exhausted by the corruption of the adults around her.

The "cases of the week" often serve as metaphors for the larger teenage experience—lost dogs and stolen darker secrets—but the overarching mystery of Lilly Kane’s death in Season 1 stands as a masterclass in serialized storytelling. It pulls back the curtain on the parents of Neptune, exposing them not as benevolent guardians but as flawed, often dangerous figures protecting their own interests. The adults in *Veronica Mars* are rarely heroes; they are disappointments. The only anchor is Veronica’s father, Keith Mars (Enrico Colantoni), and their relationship provides the show's emotional heartbeat. In a genre often defined by absent parents, Keith is present, supportive, and morally complex, offering Veronica a tether to humanity when her cynicism threatens to set her adrift.

Ultimately, *Veronica Mars* endures because it refused to talk down to its audience. It acknowledged that for a teenager, the stakes always feel like life or death—and in Neptune, they often were. It captured the specific, suffocating feeling of being an outsider looking in, realizing that the "cool crowd" isn't just exclusive, it's morally bankrupt. Decades later, Veronica’s world—where the rich buy justice and the truth is the only currency the poor have left—feels less like a high school drama and more like a prophetic vision of modern America.