✦ AI-generated review

The Promethean Gamble

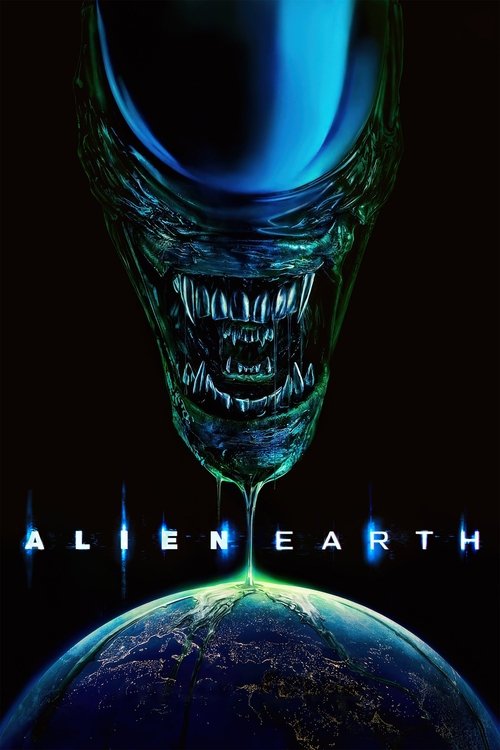

For over forty years, the *Alien* saga has functioned largely as a haunted house story: a group of blue-collar workers (or soldiers, or scientists) trapped in a tin can, picked off one by one by a phallic nightmare. It was a formula of elegant, terrifying simplicity. With *Alien: Earth*, creator Noah Hawley has done the unthinkable: he has opened the airlock. By bringing the Xenomorph to our doorstep and stretching the narrative across an eight-hour canvas, Hawley has traded the suffocating claustrophobia of the *Nostromo* for a sprawling, existential dread that feels less like a creature feature and more like a corporate techno-thriller written by Philip K. Dick.

Set in 2120, two years before Ripley’s fateful voyage, the series immediately distinguishes itself through its texture. Hawley, the auteur behind the surrealist *Legion* and the tragicomic *Fargo*, rejects the sleek, Apple-store futurism of Ridley Scott’s *Prometheus*. Instead, he commits to a "retro-futurism" that feels tactile and heavy. Earth is not a utopia; it is a humid, crowded world governed by corporate monoliths like the Prodigy Corporation. When the research vessel *USCSS Maginot* crash-lands, scarring the landscape like a wound, it brings with it not just the titular monsters, but a reckoning for a humanity that has grown arrogant in its pursuit of immortality.

The visual language here is striking. Hawley and his cinematographers juxtapose the sweaty, lived-in grit of the tactical soldiers with the sterile, terrifyingly clean laboratories of the Prodigy Corporation. The crash site itself—a smoldering ruin teeming with biological horrors—serves as the show’s visual anchor, a constant reminder of the hubris of bringing deep-space secrets home. It is a landscape where the biological and the industrial merge in grotesque fashion, echoing H.R. Giger’s original biomechanical designs but applying them to the ecosystem of Earth itself.

However, the series’ true philosophical weight rests not on the Xenomorph, but on Wendy (Sydney Chandler). As a "hybrid"—a human consciousness transferred into a synthetic body—Wendy is the series’ most fascinating creation. Chandler delivers a performance of profound vulnerability and physical precision. She is the "Lost Boy" of this narrative (a Peter Pan motif runs subtly through the show), trapped between the organic and the artificial. In one pivotal scene, as Wendy observes a captured specimen, we see a reflection of the franchise's core question: who is the real monster? Is it the creature acting on instinct, or the corporation that views both the alien and Wendy as mere assets?

Critically, *Alien: Earth* may frustrate those looking for a simple bug hunt. Hawley’s pacing is deliberate, sometimes meandering into the boardrooms of rival corporations Prodigy and Weyland-Yutani rather than staying in the vents with the monsters. The narrative occasionally buckles under the weight of its own intelligence, particularly when diving into the dense lore of transhumanism and corporate warfare. Yet, when the horror strikes, it is visceral and mean. The introduction of new creature variants, like the "Tick," proves that the franchise still has teeth, offering body horror that is intimately, sickeningly detailed.

Ultimately, *Alien: Earth* succeeds because it refuses to just play the hits. It is a series about the terrifying convergence of unchecked capitalism and unchecked evolution. It suggests that long before the Xenomorph bursts from a chest, humanity had already been hollowed out by its own greed. It is a dense, challenging, and visually spectacular entry that proves the *Alien* universe is vast enough to hold more than just screams in space.