✦ AI-generated review

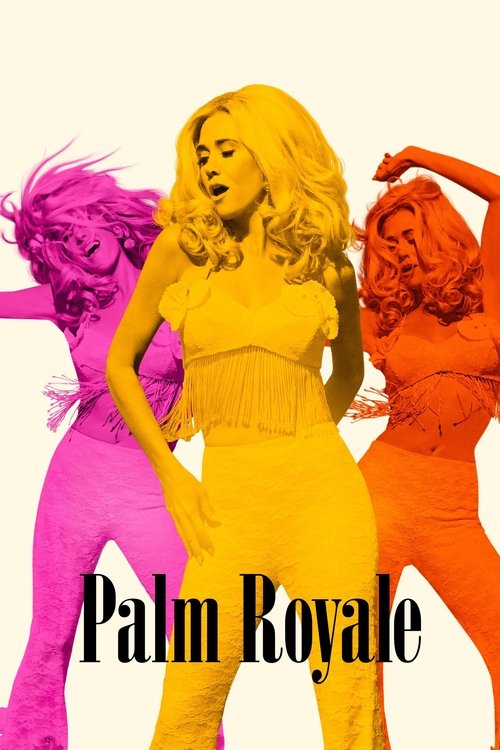

The Pastel Guillotine

If the year 1969 exists in the American cultural imagination as a split screen—Woodstock mud on one side, the pristine sterility of the moon landing on the other—*Palm Royale* chooses to look at neither. Instead, it gazes fixatedly at a third, more insidious option: the sun-bleached, hermetically sealed purgatory of Palm Beach high society. In this adaptation of Juliet McDaniel’s novel, the chaos of the late sixties is not a revolution to be joined, but a noise to be drowned out by the clinking of highball glasses. It is a series that initially presents itself as a campy confection, only to reveal a bitter, tragic aftertaste that lingers far longer than the sweetness of its visuals.

To watch *Palm Royale* is to be assaulted by a weaponized aesthetic. Creator Abe Sylvia and his production team have conjured a world that doesn’t just mimic the photography of Slim Aarons; it hallucinates it. The colors are not merely vibrant; they are aggressive. The tangerines, cyans, and lily-white upholstery create a visual landscape that feels less like a habitat and more like a suffocating beautiful cage. This is crucial to the narrative’s intent: the setting is so blindingly perfect that it renders the rot beneath it invisible to the naked eye. The camera glides over manicured lawns and poolside cabanas with a voyeuristic hunger, emphasizing that in this world, surface is substance.

At the center of this Technicolor nervous breakdown is Kristen Wiig as Maxine Simmons, a performance of such high-wire complexity that it threatens to unbalance the entire show. Maxine is not simply a social climber; she is a terrifying monument to the American religion of "positive thinking." Wiig, an actress who has always understood that the line between comedy and horror is nonexistent, plays Maxine with a desperate, vibrating intensity. She is a woman who would smile through her own execution if she thought it would get her a table by the window.

The show’s most potent visual metaphor arrives early: Maxine physically scaling the wall of the exclusive Palm Royale club. It is a moment of slapstick physicality that Wiig executes with grace, but it doubles as a brutal thesis statement. Maxine is an invasive species in a protected ecosystem. Her "posture of relentless positivity"—a phrase that haunts the character—is her armor against a society (led by a deliciously venomous Allison Janney) that views her existence as a clerical error.

Where the series transcends its "soap opera with a budget" trappings is in its willingness to let the air out of the room. The season one finale, featuring Maxine’s shattered rendition of Peggy Lee’s "Is That All There Is?", reframes the entire preceding narrative. It transforms the show from a caper about a plucky underdog into a tragedy about a woman who conquers the mountain only to find there is no air at the summit. The tragedy of Maxine is not that she might fail, but that she succeeds in entering a world that is fundamentally empty.

While the narrative occasionally buckles under the weight of its own tonal shifts—swinging wildly from feminist critique (via Laura Dern’s conscientious objector) to broad farce—the emotional core remains lucid. Ricky Martin, in a revelatory turn as the club’s closeted gatekeeper, provides the necessary mournful counterweight to Wiig’s manic energy.

Ultimately, *Palm Royale* is a study in the violence of exclusion and the hollowness of inclusion. It suggests that the American Dream, when stripped of its democratic illusions, is just a country club where everyone hates each other, but no one dares to leave because it’s too terrifying to face the world outside the gates.