The Gods of the Green RoomFor the better part of two decades, the superhero genre has operated on a scale of cosmic maximalism. We have watched gods destroy cities, timeline-hopping despots erase existence, and billionaires construct suits of armor that rival the GDP of small nations. Yet, beneath the digital sheen and the deafening third acts, the genre has begun to groan under the weight of its own ubiquity. Enter *Wonder Man*, a series that dares to suggest the most terrifying villain in the Marvel Cinematic Universe isn’t a purple alien with a gauntlet, but the crushing anonymity of the casting call.

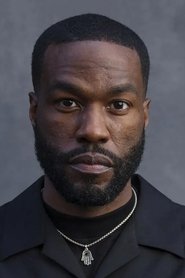

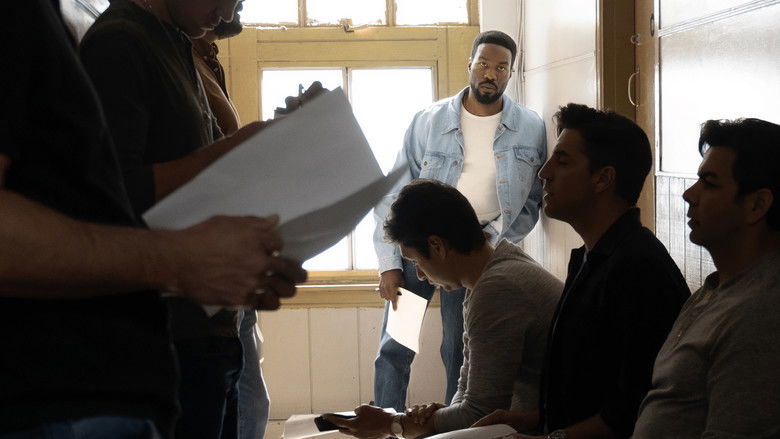

Creators Destin Daniel Cretton and Andrew Guest have not delivered a typical origin story; they have crafted a tragicomic eulogy for the "Hollywood Dream." By placing the narrative firmly under the "Marvel Spotlight" banner, they strip away the burden of interconnected homework, allowing us to focus on Simon Williams (Yahya Abdul-Mateen II)—a man whose ionic superpowers are arguably less burdensome than his desperate need for validation.

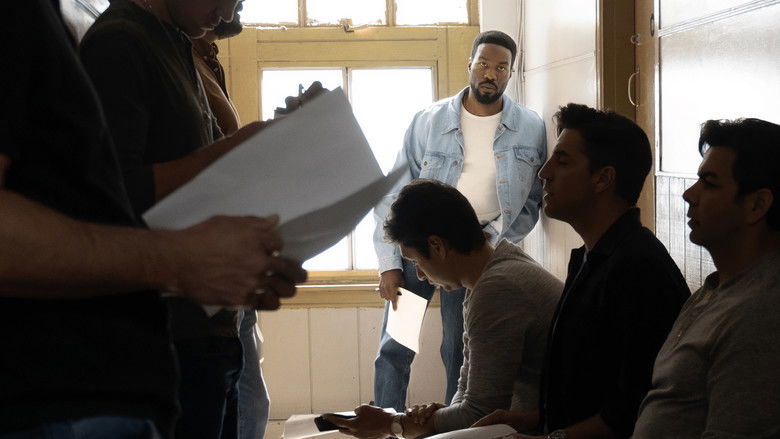

Visually, *Wonder Man* is a fascinating exercise in claustrophobia. Where most superhero media looks outward to the stars, Cretton turns the lens inward to the soundstage. The cinematography revels in the unglamorous machinery of illusion: the exposed wires of a stunt rig, the peeling paint of a dressing room, and the harsh, unforgiving lighting of an audition tape. There is a "Wes Anderson-lite" symmetry to the framing of the fictional "Wonder Man" movie production (directed by the scene-stealing Zlatko Burić as auteur Von Kovak), which clashes brilliantly with the handheld, gritty reality of Simon’s actual life.

The show treats the Hollywood backlot not as a dream factory, but as an industrial complex that chews up humanity and spits out intellectual property. When Simon signs a liability waiver denying he has superpowers—despite buzzing with lethal ionic energy—the irony is palpable. He is forced to simulate the very power he possesses because the "reality" of his strength breaks the expensive props. It is a potent metaphor for the modern actor: one must suppress their true self to fit the mold of the commercially viable product.

At the center of this satire is a profoundly human performance by Yahya Abdul-Mateen II. He imbues Simon with a simmering, melancholy dignity. This is not the swaggering hero we are used to; this is a man exhausted by the hustle. His chemistry with Ben Kingsley’s Trevor Slattery is the show’s beating heart. Kingsley, reprising his role as the failed actor-turned-terrorist-proxy, is no longer just a punchline. Here, he is a ghost of Christmas Future for Simon—a warning of what happens when the industry consumes you whole. Their dynamic is less "buddy cop" and more *Waiting for Godot*, two performers waiting for a cue that may never come.

The decision to focus on the stunt community—the invisible labor behind the spectacle—adds a layer of grit that grounds the fantastical elements. The action sequences are designed to look "wrong" in the most fascinating way; we see the seams, the mistakes, and the physical toll, reminding us that even in a universe of magic, gravity still applies.

Ultimately, *Wonder Man* succeeds because it refuses to treat its protagonist as a vessel for plot. It is a character study of a man who can withstand a missile strike but crumbles under the silence of a phone that won’t ring. In an era where the superhero genre is often accused of being an assembly line, *Wonder Man* stops the conveyor belt to ask the workers if they are okay. It is a bold, bizarre, and beautiful deconstruction of the mask, proving that sometimes the hardest role to play is simply yourself.