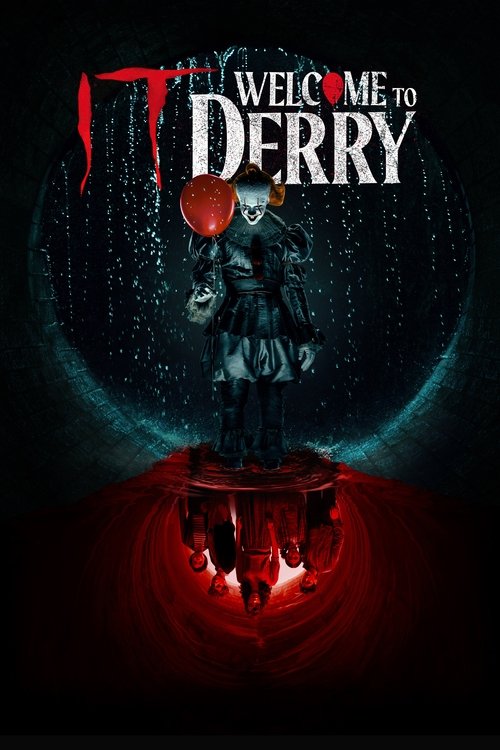

The Architecture of FearThere is a moment in the middle of *IT: Welcome to Derry* where the camera lingers not on a monster, but on a mundane street corner in 1962 Maine. The lighting is sickly, bathed in the tungsten glow of a dying afternoon, and for a split second, the town itself seems to inhale. It is a reminder that in the architecture of Stephen King’s universe, the monster is rarely just the clown in the storm drain; the monster is the drain itself, the concrete, the apathy of a community that allows rot to fester. Showrunners Andy and Barbara Muschietti, returning to the world they so vividly modernized in their two-part film saga, have shifted their gaze from the coming-of-age trauma of the Losers' Club to a broader, more systemic infection. The result is a series that feels less like a prequel and more like an autopsy of an American nightmare.

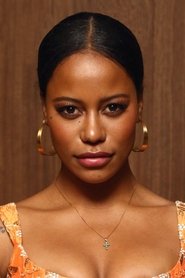

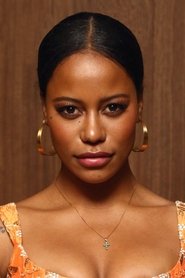

The narrative anchor this time is not a band of plucky children, but the Hanlon family—ancestors of the films' Mike Hanlon—who arrive in Derry bearing the weight of hope and the scars of racial tension. By centering the Black experience in a predominantly white, secretive New England town, the series adds a layer of social horror that King’s text only grazed. When Taylour Paige and Jovan Adepo are on screen, the "monster" is frequently just the neighbor across the fence. The supernatural horror, when it arrives, acts as an accelerant to existing human cruelty. The Muschiettis’ visual language remains impeccable; they treat the period setting not as a nostalgic playground, but as a suffocating cage of mid-century repression.

However, the series struggles occasionally under the weight of its own mythology. The introduction of "Operation Precept," a Cold War military subplot involving General Shaw (James Remar), attempts to give a pseudo-scientific explanation to the town's evil. It is a risky gamble. Part of Pennywise’s terror has always been his cosmic inexplicability—an ancient, formless malice that defies logic. By introducing military men hunting for a "weapon" to end the Cold War, the show sometimes risks reducing the eldritch to the tactical. Yet, when the series reconnects with its horror roots—specifically in the depiction of the infamous "Black Spot" tragedy—it achieves a level of devastation that transcends genre tropes. The fire is not just a plot point; it is a howling wound in the town’s history, rendered with a brutality that makes the viewer want to look away, but unable to do so.

Bill Skarsgård’s return as Pennywise is, predictably, magnetic. There was a fear that overexposure would dull the clown’s teeth, but Skarsgård finds new notes of sadism here. He is less of a jump-scare machine and more of a psychological parasite, feeding on the specific anxieties of adults rather than just the phobias of children. But the true heart of *Welcome to Derry* lies in its refusal to offer easy comfort. In the films, we knew the kids would (mostly) survive to fight another day. Here, in the prequel, we are watching a tragedy we know is coming. We know the cycle will not be broken in 1962. This inevitability gives the series a mournful, heavy atmosphere. It is a story not about defeating evil, but about how a town learns to live with it, silence it, and eventually, feed it.