✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of a Drowning

Disaster cinema typically operates on a simple, adrenaline-fueled contract: we pay to see the spectacle of destruction, followed by the catharsis of survival. But in *Heweliusz*, director Jan Holoubek (*The Mire*, *High Water*) rejects this Hollywood binary. He is not interested in the pornography of wreckage, but in the autopsy of a system. By dramatizing the 1993 sinking of the MS Jan Heweliusz—the worst peacetime maritime disaster in Polish history—Holoubek creates a suffocating study of national trauma that feels less like *The Perfect Storm* and more like a maritime *Chernobyl*.

Holoubek’s visual language is bifurcated, splitting the world into two distinct, equally lethal environments. The first is the Baltic Sea itself. Cinematographer Bartłomiej Kaczmarek shoots the storm not as an adventure, but as a sensory assault. The camera does not float objectively; it is battered, submerged, and frozen. The color palette is a bruising mix of slate greys, aggressive teals, and the pitch black of a winter night. These scenes are terrifyingly visceral, stripping the characters of their agency and reducing them to desperate biological entities fighting for air.

However, the true horror of *Heweliusz* emerges in its second environment: the dry, beige, smoke-filled rooms of the inquiry commissions on land. Here, the camera creates a different kind of claustrophobia. If the sea drowns the body, the bureaucracy drowns the truth. Holoubek uses static, lingering shots in these administrative spaces to emphasize the stagnation of a post-communist Poland struggling to shed its old skin. The year is 1993—technically a new era of democracy—but the series sharply illustrates how the instincts of the old regime (cover-ups, scapegoating, and the protection of "the institution" over the individual) remain intact. The dry land feels just as treacherous as the open water.

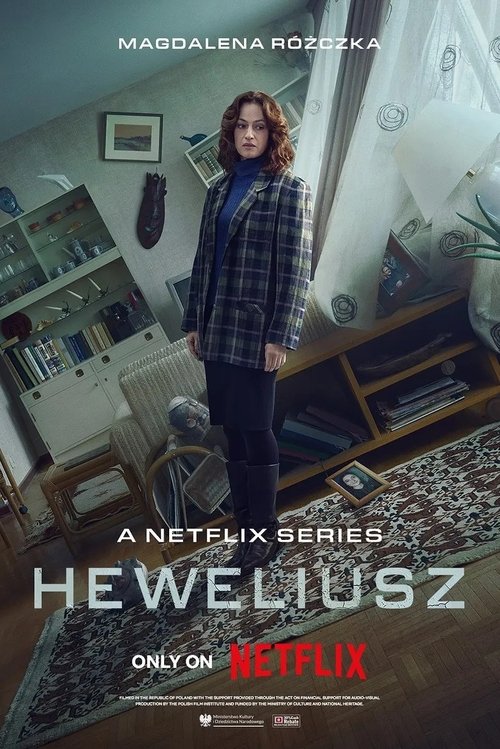

At the narrative’s heart lies a searing exploration of survivor’s guilt and the burden of those left behind. The script, written by Kasper Bajon, wisely avoids a single protagonist, instead weaving a tapestry of grief. Yet, the performance of Michał Żurawski as the off-duty captain, Piotr Binter, offers a devastating anchor. Żurawski plays Binter with a hollowed-out intensity; he is a man haunting his own life, carrying the spectral weight of the colleagues he could not save. Parallel to him is Jolanta Ułasiewicz (Magdalena Różczka), the widow fighting against a narrative convenient for the state: that the dead captain was solely to blame. Their struggle is not just against grief, but against a "paper reality" that seeks to rewrite history before the bodies are even recovered.

There is a moment in the series where the sheer weight of the ferry—nicknamed "the floating coffin" due to its instability—becomes a metaphor for the state itself: patched up with concrete, top-heavy, and doomed by negligence long before the first wave hit. The tragedy, the film argues, did not begin with the wind; it began with the silence of those who knew better.

*Heweliusz* is a dense, demanding watch that refuses to offer easy closure. It posits that while a ship sinks only once, the survivors continue to drown for decades. In the landscape of modern European television, this is a masterclass in how to turn a historical footnote into a universal parable about the cost of lies.