The Architecture of HopeTo inherit a utopia is a burden; to rebuild one is a crucible. This is the central tension that animates *Star Trek: Starfleet Academy*, a series that arrives not merely as the twelfth entry in a sixty-year-old canon, but as a deliberate interrogation of what "Starfleet" means when the institution itself has become a ghost story. Set in the 32nd century—an era defined by the post-apocalyptic silence of "The Burn" and the subsequent, fragile reconstruction of the Federation—the show eschews the confident swagger of the Kirk or Riker eras. Instead, it offers us something more precarious and infinitely more human: the awkward, messy, and terrifying process of learning how to believe in the future again.

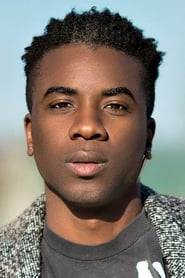

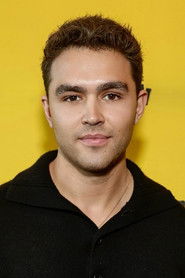

Critics and skeptics were quick to weaponize the term "CW Trek" before the premiere, bracing for a trivialized teen drama wrapped in polyester uniforms. And while the pilot certainly indulges in the vernacular of adolescence—blossoming rivalries, dorm-room anxieties, and the raw nerve of first loves—to dismiss it as such is to miss the forest for the cherry blossoms. Under the stewardship of showrunners Alex Kurtzman and Noga Landau, the "teen angst" serves a vital narrative function. These cadets, played with frenetic energy by a diverse ensemble including Sandro Rosta and Bella Shepard, are not merely students; they are children of a fractured galaxy. They have no memory of a Golden Age. Their optimism is not inherited; it is a muscular, defiant choice made in the face of cynicism.

Visually, the series creates a fascinating dialectic between the sterile and the organic. The production design leverages the programmable matter and floating interfaces of the *Discovery* era, yet grounds them in the terrestrial warmth of a San Francisco that feels lived-in and lush. The Academy itself is filmed not as a military installation, but as a sanctuary. When the action shifts to the *USS Athena*, the show’s "teaching hospital" in the stars, the cinematography tightens. The vast emptiness of space feels more dangerous here than in previous iterations, precisely because the crew is so inexperienced. We are not watching seasoned veterans solve technobabble puzzles; we are watching frightened prodigies fumble toward competence, making the stakes feel refreshingly lethal.

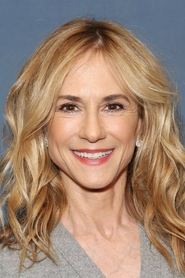

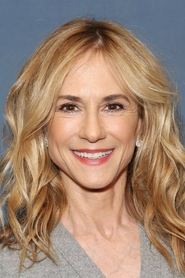

However, the gravitational center of the series is undoubtedly Holly Hunter as Chancellor Nahla Ake. Hunter brings an idiosyncratic gravity to the Captain’s chair that we haven't seen before. She plays Ake not as a monolithic commander, but as a pedagogue burdened by history. Her performance is quiet, observational, and laced with a steeliness that suggests she knows the cost of every order she gives. Watching her verbally spar with Paul Giamatti’s Nus Braka—a villain whose malice is intellectual rather than cartoonish—elevates the series into a genuine drama of ideas. Giamatti does not chew scenery; he deconstructs the Federation’s ideology, forcing both the cadets and the audience to question if the "utopia" is worth the price of admission.

Ultimately, *Starfleet Academy* succeeds because it understands that the uniform does not make the officer. In previous series, the competence of the crew was a given; here, it is the objective. The series asks us to be patient with imperfection, to watch characters fail, and to understand that the Federation isn't a government, but an agreement to be better. It is a show about the heavy lifting required to keep the lights on in civilization, argued with empathy and a surprising amount of soul. It may wear the trappings of a coming-of-age story, but its heart is ancient, beating with the timeless hope that the next generation might just get it right.