✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of Desperation

In the mid-2000s, television underwent a structural revolution. While *Lost* was teaching audiences to decipher metaphysical riddles and *24* was accelerating the pulse of the post-9/11 security state, *Prison Break* arrived with a proposition that was deceptively simple: a man breaks into prison to break his brother out. Yet, to view Paul Scheuring’s 2005 creation merely as a procedural thriller is to miss its deeper obsession with design, control, and the terrifying fragility of the human body against the weight of the state.

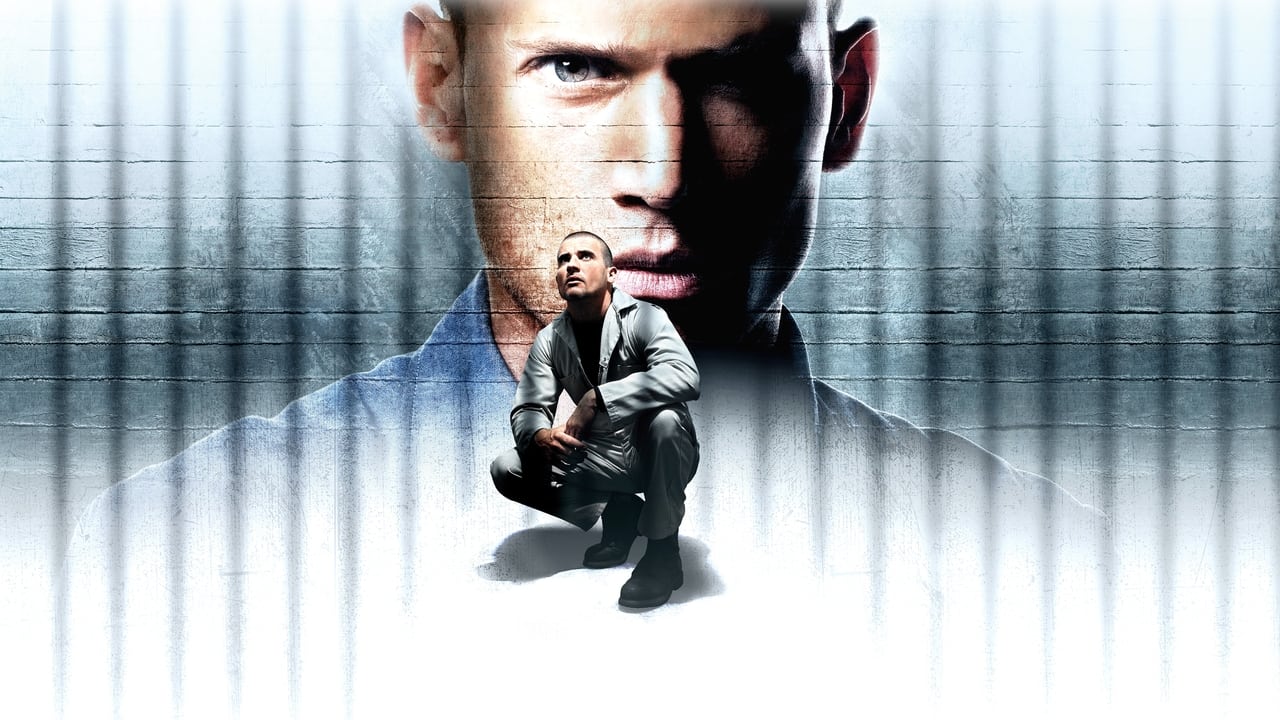

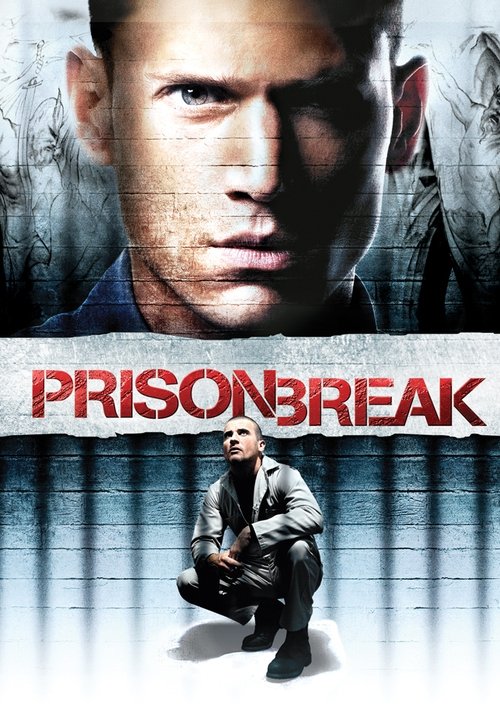

At its heart, *Prison Break* is a modern retelling of the myth of the labyrinth, but with a crucial inversion: the hero, Michael Scofield (Wentworth Miller), does not enter the maze to slay the minotaur, but to rescue him. The minotaur here is his brother, Lincoln Burrows (Dominic Purcell), a man wrongly condemned to die by the electric chair—a blunt instrument of a corrupted justice system. If Lincoln represents the brute physical reality of incarceration, Michael is the intellectual transcendence of it. He is not a warrior; he is a structural engineer. In a genre typically dominated by muscle and firepower, Scofield weaponizes architecture.

The show’s defining visual motif—and perhaps one of the most iconic images in television history—is the tattoo. Covering Scofield’s upper body is a baroque tapestry of angels and demons that conceals the blueprints of Fox River State Penitentiary. It is a stroke of narrative genius that transforms the protagonist’s body into the text of the story itself. The escape plan is not a file on a computer or a hidden notebook; it is etched into his skin, making his very existence the key to freedom. This corporeal map forces the camera to linger on the human form, emphasizing the vulnerability of flesh in an environment built of steel and concrete.

Visually, the series operates in a palette of sweaty, industrial blues and sickness greens, creating a submerged, aquarium-like atmosphere that enhances the sense of claustrophobia. The prison is shot not just as a setting, but as an antagonist—a panopticon where every sightline is a threat. Into this pressure cooker, the writers introduce a gallery of grotesques who function less like traditional villains and more like dangerous variables in Scofield’s equation. The most indelible of these is Theodore "T-Bag" Bagwell (played with Shakespearean malice by Robert Knepper), a white supremacist predator who serves as the chaos inherent in any perfect system. Scofield’s struggle is often less about the guards and more about navigating the moral sewage of having to align with monsters to save a saint.

Miller’s performance as Scofield is an exercise in restraint. He plays the character with a quiet, almost spectral intensity, utilizing a "low latent inhibition" that forces him to process every detail of his environment. He is a man burdened by the inability to ignore the world’s mechanics. While the supporting cast often chews the scenery, Miller remains the calm eye of the storm, his stillness acting as a counterweight to the kinetic frenzy of the plot.

Critics often note that *Prison Break* inevitably struggled to maintain its momentum in later seasons—once the break occurs, the titular tension dissolves. However, the inaugural season remains a singular achievement in serialized tension. It captures a specific anxiety of the modern age: the fear that the systems designed to protect us—law, architecture, government—are actually cages, and that the only way to survive them is to dismantle them from the inside out. It is a pulp thriller with the soul of a Greek tragedy, arguing that the bond of brotherhood is the only structure strong enough to withstand the crushing weight of the world.