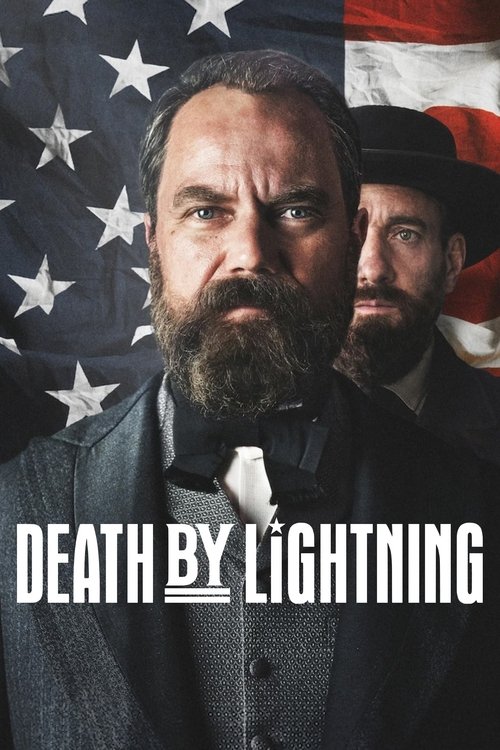

✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of a Lost Future

James A. Garfield is the phantom limb of American history. He exists in the collective consciousness mostly as a trivia answer—the second president to be assassinated, a man who served mere months before a bullet cut him down. In *Death by Lightning*, creator Mike Makowsky and director Matt Ross do not merely dust off a history book; they perform an autopsy on a timeline that was brutally severed. This four-part limited series is less a biopic and more a tragedy of colliding particles: the immovable object of integrity meeting the unstoppable force of delusion.

The series opens with a jarring, anachronistic prologue set in 1969—a brain in a jar clattering to the floor of a medical museum. It is a brilliant visual thesis statement: history is messy, physical, and often reduced to grotesque artifacts. From there, Ross transports us to the suffocating texture of the 1880s. The visual language here is not the sepia-toned nostalgia of Ken Burns, but a grimy, lived-in reality. The camera lingers on the sweat of a smoke-filled backroom and the mud of a Washington street, grounding high-stakes politics in the visceral filth of the era. This aesthetic choice is crucial; it underscores that the "Gilded Age" was often just gold paint flaking off a rotting beam.

At the center of this rot stands—or rather, slithers—Matthew Macfadyen as Charles Guiteau. Macfadyen, fresh from his triumph in *Succession*, repurposes his gift for playing beta-male desperation into something far more harrowing. His Guiteau is not a mustache-twirling villain but a terrifyingly recognizable modern figure: the mediocre man convinced of his own main-character energy. Macfadyen plays him with a vibrating, manic pathos. When Guiteau practices speeches in front of a mirror or stalks the corridors of power, we don't see a monster; we see a void desperately trying to fill itself with importance. It is a performance of profound discomfort, eliciting not sympathy, but a pity that curdles into horror.

Opposite him is Michael Shannon’s Garfield, a performance of remarkable restraint. Shannon, often known for his intensity, here plays against type as a man of quiet, reluctant nobility. He embodies the "what if" of the series. Garfield is presented not as a politician, but as a scholar and a humanist drafted into a war he didn't start. Shannon captures the exhaustion of a man trying to introduce logic to an asylum. The chemistry between these two—the man who wants to serve the public and the man who wants the public to serve him—drives the narrative toward its inevitable, tragic conclusion.

Perhaps the series' most surprising triumph is Nick Offerman as Chester A. Arthur. Initially introduced as a corrupt, drunken buffoon—a creature of the "spoils system" who shouts for "Music! Fighting! Sausages!"—Offerman imbues him with a shocking soulful arc. He becomes the audience surrogate, the man who realizes too late that governance is not a game.

*Death by Lightning* ultimately succeeds because it refuses to treat the assassination as a mere plot point. Instead, it frames the violence as a theft. By meticulously building up Garfield’s potential—his stance on civil rights, his intellectual rigor—the series makes his death feel like a contemporary wound. It suggests that the chaos of the present day is not an anomaly, but a recurring infection. In watching the destruction of a decent man by a delusional narcissist, we are forced to confront the fragility of our own institutions. The series argues that progress is not a straight line; it is a precarious path, always one lightning strike away from darkness.