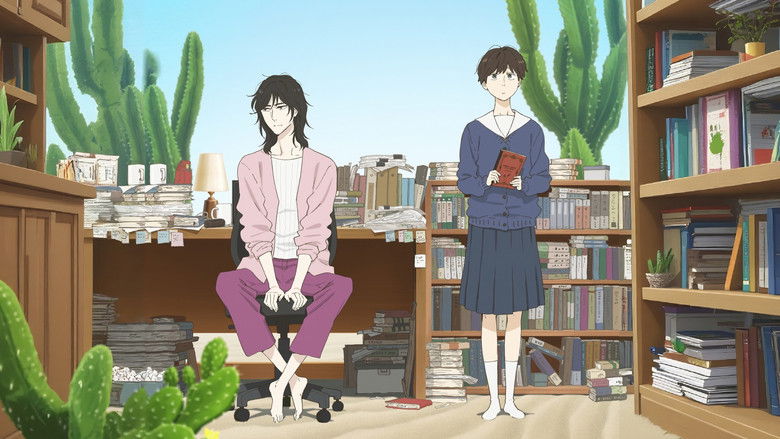

The Cartography of GriefIn the vast, often cacophonous landscape of modern animation, silence is a risk. Most series rush to fill the void with exposition or spectacle, fearing the audience might look away if the screen isn't exploding. *Journal with Witch* (adapted from Tomoko Yamashita’s celebrated manga *Ikoku Nikki*) dares to do the opposite. Premiering in the winter of 2026 under the careful direction of Miyuki Oshiro at Studio Shuka, this series is not an escape from reality, but a confrontation with its most uncomfortable quietudes: the death of a family member, the friction of cohabitation, and the terrifying realization that adults often have no more answers than the children they guard.

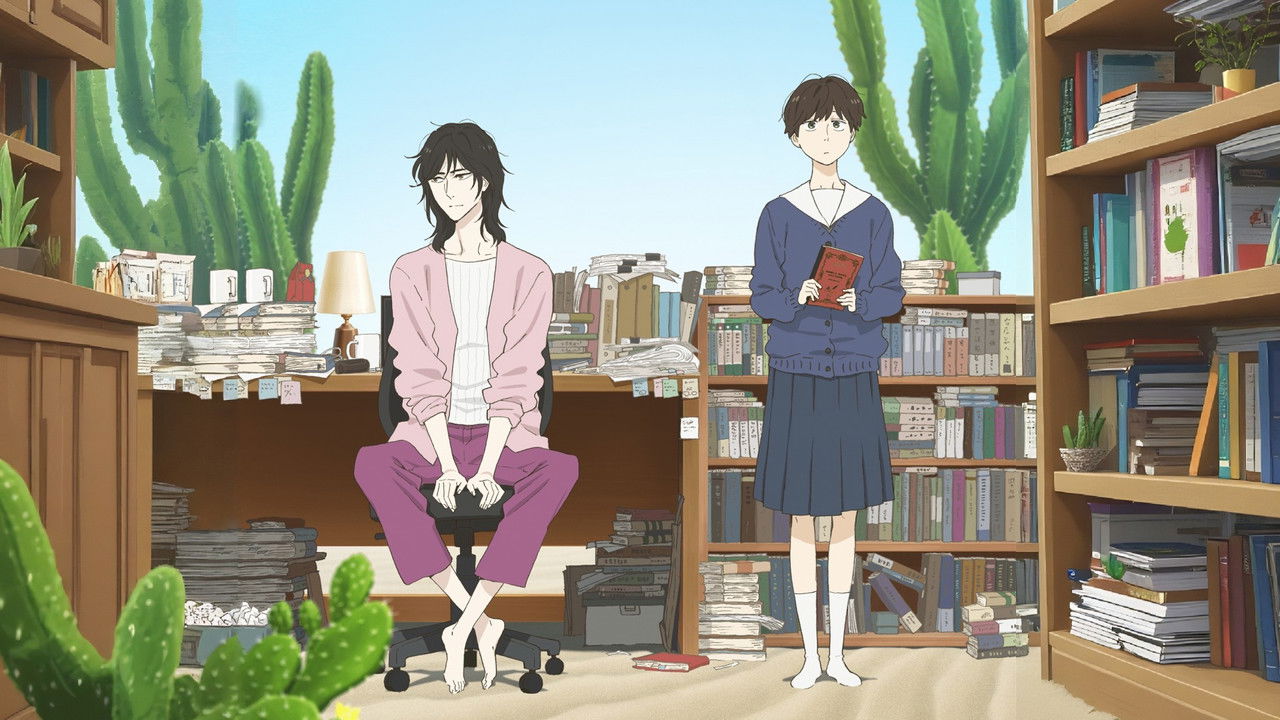

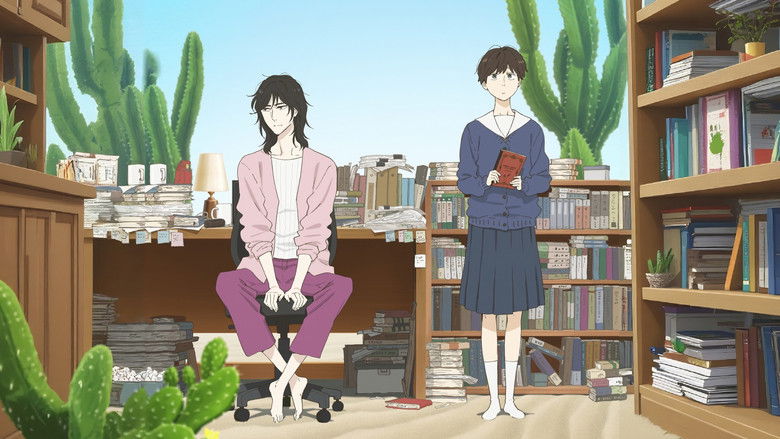

The visual language of *Journal with Witch* is defined by what it leaves out. Studio Shuka, known for the ethereal *Natsume’s Book of Friends*, utilizes a "less is more" approach here that feels almost architectural. The backgrounds are often washed out or minimalist, reflecting the internal "desert" that the protagonist, Makio Koudai, frequently references. This is not laziness; it is a stylistic choice to mirror the numbness of grief. When the score by Kensuke Ushio—a composer who specializes in the sounds of isolation—creeps in with its discordant, glitchy piano, the domestic space of Makio’s apartment feels less like a home and more like a waiting room for two souls stranded in transit.

The narrative hook is deceptively simple: Makio, a socially maladjusted novelist in her 30s, takes in her 15-year-old niece, Asa, after the sudden death of Asa’s parents. But this is not the heartwarming "found family" trope we have been trained to expect. Makio did not love her sister (Asa’s mother); in fact, she actively disliked her. The scene at the funeral, where Makio interrupts the relatives’ bureaucratic squabbling over Asa not out of love, but out of a sudden, prickly sense of justice, is a masterclass in character definition. Miyuki Sawashiro’s vocal performance here is jagged and reluctant, stripping away the veneer of the "benevolent guardian." She offers Asa a roof, not a hug.

At its heart, the series is a study of neurodivergence and emotional literacy. Makio is coded as someone who experiences the world with overwhelming intensity, necessitating her hermit-like withdrawal. Her struggle isn't just about raising a teenager; it's about the intrusion of "the other" into her carefully curated sanctuary. Conversely, Asa (voiced with profound vulnerability by newcomer Fuko Mori) is navigating the numbness of shock. The "journal" of the title becomes the third main character—a tool Makio offers Asa not to "fix" her grief, but to give it a physical form. The act of writing becomes a way to map the wilderness of their emotions, proving that language is sometimes the only bridge across the chasm separating two people.

*Journal with Witch* posits a radical idea for the *Josei* genre: that love does not require understanding. Makio and Asa are, as the Japanese title *Ikoku Nikki* ("Diary of a Strange Land") suggests, citizens of different countries trying to learn each other's customs. The series refuses to rush their intimacy. It allows them to be awkward, resentful, and silent. In doing so, it achieves a rare emotional resonance that feels less like watching a story and more like remembering a difficult season of one's own life. It is a quiet triumph, reminding us that sometimes the bravest thing one can do is simply stay in the room with someone else's pain.