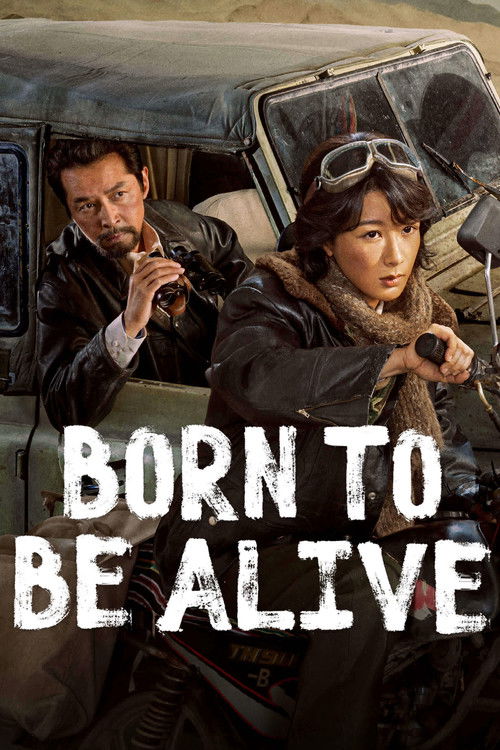

The Tree of Life in a Barren LandIn the vast, oxygen-thin expanse of the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau, silence is not an absence of sound, but a geological weight. It presses down on the characters of *Born to Be Alive* (*Sheng Ming Shu*), molding them as ruthlessly as the wind sculpts the sandstone. Director Li Xue, a filmmaker who earned his stripes orchestrating the intricate court politics of *Nirvana in Fire*, here trades the claustrophobic interiors of power for the terrifying openness of the wild. The result is a series that feels less like a police procedural and more like a spiritual western, where the law is a fragile concept against the ancient, indifferent majesty of the mountains.

Li Xue’s visual language in *Born to Be Alive* is a study in isolation. Working with the prestigious Daylight Entertainment team, he eschews the glossy, over-lit aesthetic common in modern C-dramas for a gritty, textured realism. The camera lingers on the cracked skin of the patrol officers and the blood-stained snow of the poaching grounds. There is a tactile quality to the filmmaking; you can almost feel the biting cold and the stinging sand. The cinematography captures the duality of the setting: it is a place of breathtaking beauty, where the sky feels close enough to touch, yet it is also a graveyard for both the innocent Tibetan antelopes and the souls who try to protect them. The landscape is not merely a backdrop; it is the antagonist, the judge, and the jury.

At the center of this storm is Bai Ju, played with searing intensity by Yang Zi. Shedding her idol-drama polish, she delivers a performance of raw, physical commitment. Bai Ju is a woman carved from the Gobi desert itself—unyielding, jagged, and deeply scarred. The narrative arc, spanning decades from the lawless 1990s to the present day, demands a transformation that is internal as much as external. We watch her evolve from a defiant orphan adopted by highway engineers into a hardened mountain patrol officer, haunted by the ghost of her mentor, Dorje.

The series finds its emotional anchor in the relationship between Bai Ju and Dorje (a magnetic, if spectral, turn by Hu Ge). Their bond transcends the typical romantic tropes; it is a shared covenant of guardianship. One of the most discussed sequences involves the discovery of a slaughtered herd of antelopes—a scene of grotesque violence rendered with a somber, respectful quietness. Bai Ju’s reaction is not hysterical grief but a calcifying resolve. It is in these moments that Li Xue excels, allowing the actors' silence to speak louder than the script. The mystery of Dorje’s disappearance serves as the narrative engine, but the fuel is the generational trauma of a land exploited for its resources, be it the skins of endangered animals or the coal beneath the earth.

However, the series is not without its stumbling blocks. In its ambition to cover decades of eco-political shifts, the pacing occasionally buckles. The transition between the high-stakes survivalism of the 90s and the modern-day investigation can feel jarring, a shift in genre that the script struggles to bridge seamlessly. Yet, the emotional continuity provided by Bai Ju’s relentless pursuit of truth holds the disparate timelines together.

Ultimately, *Born to Be Alive* is a requiem for the unsung heroes of environmental protection. It posits that true heroism is not found in glorious battles, but in the lonely, freezing vigils held on the edge of the world. Li Xue has crafted a work that demands patience, rewarding the viewer with a profound meditation on what it means to dedicate one’s life to something larger than oneself. In a year of loud blockbusters, this series has the quiet, enduring power of a mountain range.