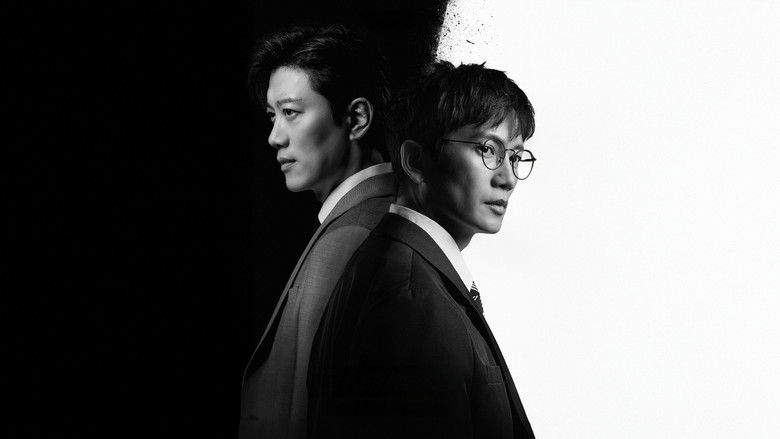

The Architecture of RegretThe fantasy of the "do-over" is perhaps the most seductive trope in modern Korean pop culture. In a society hyper-focused on competition and the permanence of failure, the *hwe-gwi* (regression) genre offers a digital-age balm: the chance to respawn with a cheat sheet. *The Judge Returns*, premiering this January amidst a flurry of similar "second life" narratives, risks drowning in the very cliché it inhabits. Yet, under the direction of Lee Jae-jin, the series attempts to elevate itself from a mere revenge fantasy into a grimmer, more textural study of moral decay and sudden rehabilitation.

The premise is deceptively simple: Lee Han-young (played by the evergreen Ji Sung) is a judge who degraded himself into a "slave" for a monolithic law firm, only to die and wake up ten years in the past. However, Director Lee Jae-jin does not treat this temporal shift as a mere plot device for "cider" (a Korean term for cathartic, carbonated justice). Instead, he frames the courtroom as a claustrophobic theater of memory. The visual language of the series, particularly in the pilot episodes, emphasizes the suffocating architecture of the legal system. The camera often lingers on the high ceilings and the isolating judge’s bench, suggesting that Han-young is not just fighting corrupt oligarchs, but the institution that made his corruption so easy in the first place.

The series’ greatest asset, and its necessary anchor, is Ji Sung. Having already explored the legal anti-hero in *The Devil Judge*, Ji Sung here strips away the flamboyant theatricality of that previous role to find something more pathetic and human. His Lee Han-young is not a chaotic force of nature but a man exhausted by his own compromises.

In the early sequences depicting his "first life," Ji Sung plays Han-young with a hunched, hollow-eyed subservience that is painful to watch. When the timeline resets, the performance shifts not into superheroic confidence, but into a desperate, frantic urgency. He is a man who remembers the taste of the dirt he was forced to eat. The tension in the series comes not from *if* he will win—the regression genre guarantees his victory—but from the psychological toll of wearing a mask of righteousness over a soul that remembers its own rot.

This internal conflict is externalized in his relationship with prosecutor Kim Jin-ah (Won Jin-ah). While she represents the uncompromising idealism of the present, Han-young represents the cynical pragmatism of the future. Their clashes in the courtroom are not just legal debates but collisions of two different time zones. The director wisely uses these moments to slow down the frenetic pace of the regression plot, allowing the actors to breathe life into the ethical dilemmas at play. Can true justice be delivered by a man who is technically cheating the timeline?

Ultimately, *The Judge Returns* is trying to answer a question that haunts the genre: Does fixing the past actually heal the person? While the show indulges in the requisite genre thrills—the takedowns of arrogant chaebols and the overturning of unjust verdicts—there is a melancholy undercurrent here. It suggests that even with a time machine, the hardest judge to satisfy is the one staring back from the mirror. In a sea of "content" designed to be consumed and forgotten, this series makes a valiant argument for the art of remembering.