✦ AI-generated review

The Rehearsal of Villainy

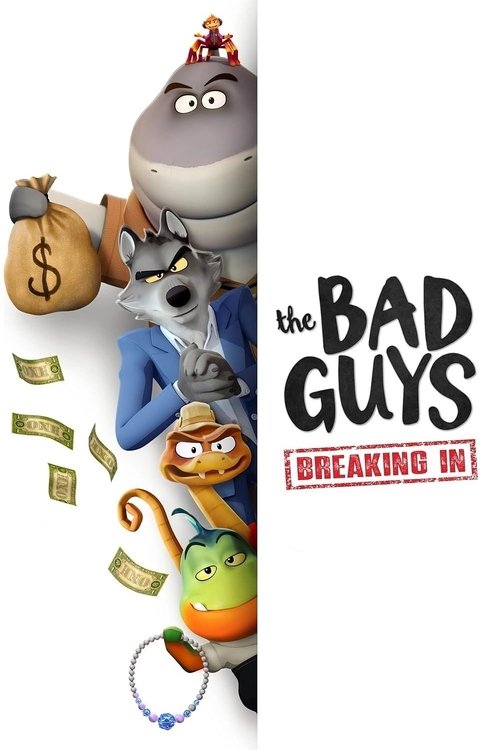

In the modern cinematic landscape, the prequel is often a trap. It tends to be a teleological exercise where we watch characters confusingly stumble toward a destiny we already know they attain, draining the narrative of genuine stakes. However, *The Bad Guys: Breaking In* (2025) manages to sidestep this fatigue by reframing the origin story not as a tragedy or a prophecy, but as a workplace comedy about incompetence. If the 2022 film presented Mr. Wolf and his crew as the Ocean’s Eleven of the animal kingdom—suave, synchronized, and effortlessly cool—this Netflix series peels back the veneer to reveal the sweaty, desperate rehearsals that came before the applause.

The series, executive produced by Bret Haaland and Katherine Nolfi, posits a delightful thesis: "cool" is a construct, and "bad" is a job you have to learn. The pilot establishes this brilliantly with a visual gag that serves as the show’s spiritual anchor. We see the crew speeding away in a getaway car, bracing for the thrill of a police chase. Mr. Wolf preens, ready for the notoriety. But the sirens wail right past them, chasing a *real* criminal down the block. In that moment of deflation, the show finds its true subject. This is not a story about crime; it is a story about the crushing anxiety of irrelevance.

Visually, the transition from the feature film’s lush, "Spider-Verse"-adjacent aesthetic to a streaming series budget is noticeable, but not entirely unwelcome. The film’s fluid, frame-dropping style has been replaced by a stiffer, more traditional TV animation rigidity. A cynic might call it a downgrade; a generous critic might argue it fits the narrative. These characters are not yet the fluid, dynamic figures of the movie. They are sketchier, rougher around the edges, and their world feels appropriately smaller and flatter. The "stiff" animation mirrors their awkwardness—they are literally not moving with the grace of professional felons yet.

The voice cast, entirely replaced from the film, also reshapes the energy. Without the Hollywood baritone of Sam Rockwell, Michael Godere’s Mr. Wolf feels less like a weary celebrity and more like a chaotic middle manager trying to keep a startup afloat. This Wolf is needier, louder, and more prone to panic. It changes the dynamic of the crew from a slick machine to a dysfunctional family. The heart of the series lies in this friction—the irony that to become the "Bad Guys," they must first learn to be good partners. The heist mechanics—breaking into candy factories or stealing jetpacks—are merely the playground equipment on which they learn to share and trust.

Ultimately, *The Bad Guys: Breaking In* is a series about "imposter syndrome" with fur. It lacks the cinematic texture and the emotional weight of its big-screen predecessor, trading deep character arcs for episodic slapstick. Yet, there is something endearing about watching the rehearsal rather than the performance. It reminds us that before the legend, there is always the struggle, the error, and the embarrassing silence when the police car drives right past you.