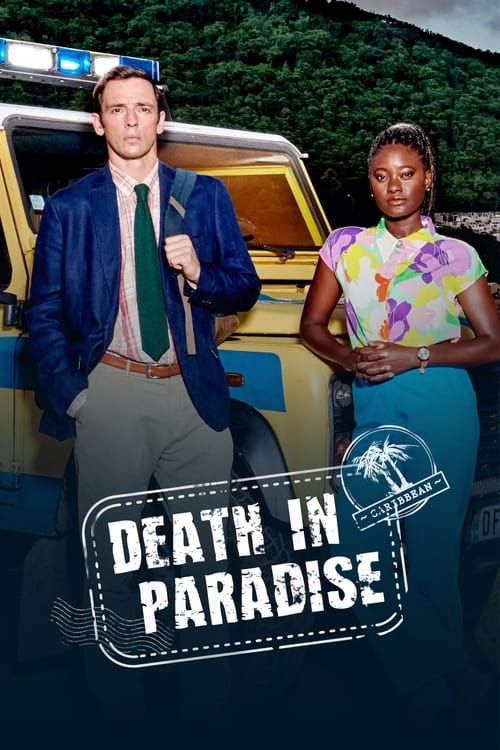

The Ritual of Sun-Drenched DeathTo criticize *Death in Paradise* for being formulaic is to criticize a sonnet for having fourteen lines. Since its debut in 2011, this BBC stalwart has not merely survived on the rigid structure of the "cosy mystery"; it has weaponized it. In an era of television defined by sprawling, anxiety-inducing prestige dramas, there is something almost radical about a show that promises—and delivers—the exact same narrative arc, week after week, for over a decade. It is a procedural lullaby, set to a reggae beat.

Visually, the series is an exercise in high-contrast escapism. Filmed in Guadeloupe (doubling for the fictional Saint Marie), the show’s aesthetic is aggressively bright. The turquoise waters and saturated greens are not just a backdrop; they are the primary antagonist. For the succession of British detectives who are parachuted in—from the prickly Richard Poole to the neurotic Neville Parker, and now the sharp-edged Mervin Wilson (Don Gilet)—the heat is a physical oppressor. The director’s lens frequently juxtaposes the gruesome (a body in a locked room) with the idyllic (a swaying palm tree), creating a surreal "holiday from hell" dissonance. This visual language reinforces the central joke: paradise is beautiful, but it is also inconvenient, sweaty, and surprisingly lethal.

However, beneath the lighthearted banter and the "fish-out-of-water" comedy lies a more complex, and often contentious, conversation about colonialism and class. For years, the show adhered to a specific, somewhat uncomfortable trope: the brilliant, eccentric white British male arriving to "fix" the chaos that the local, predominantly Black police force could not.

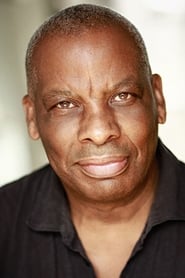

Yet, to dismiss it entirely as a colonialist relic is to ignore the subtle gravitation of the show’s true center. While the Detective Inspectors rotate through the "shack" on the beach, the island’s permanent residents—specifically Commissioner Selwyn Patterson (the majestic Don Warrington) and Catherine Bordey (Élisabeth Bourgine)—provide the show’s emotional ballast. Warrington, in particular, plays Patterson not as a subordinate, but as a tolerating monarch. His weary skepticism of the "British method" often feels like the show winking at its own absurdity. As the cast has evolved, introducing characters like Shantol Jackson’s ambitious DS Naomi Thomas and Ginny Holder’s Darlene Curtis, the series has slowly shifted the competency balance, allowing the "local" team to be as brilliant as the imported eccentric.

The emotional core of *Death in Paradise*, however, is not the murder, but the loneliness of the transient detective. Whether it is grief, social anxiety, or a failed marriage, the lead investigator is always broken. Saint Marie becomes a purgatory where they must solve others' problems to avoid facing their own. The "denouement scene"—that Hercule Poirot-style gathering of suspects—is not just about catching a killer; it is the only moment the chaotic world makes sense to the protagonist.

Ultimately, *Death in Paradise* succeeds because it understands the therapeutic value of order. In a real world filled with senseless tragedies, there is a profound comfort in a universe where the killer is always caught within 60 minutes, the motive is always understandable, and the sun always sets over a shared drink at Catherine’s bar. It is not challenging art, but it is a masterclass in the art of reassurance.