✦ AI-generated review

The Blood of the Ludus

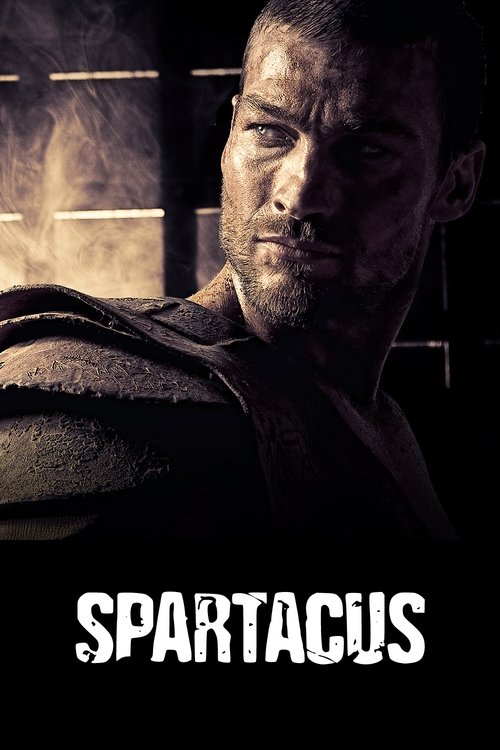

When *Spartacus: Blood and Sand* premiered in 2010, it was easy—and perhaps intended—for critics to dismiss it as a tawdry, testosterone-fueled fever dream. Visually indebted to Zack Snyder’s *300* and narrative-wise a pulpy cousin to HBO’s *Rome*, the series initially presented itself as a spectacle of digital gore and soft-core erotica. Yet, to view *Spartacus* solely through the lens of its excesses is to miss one of the most remarkably constructed tragedies of modern television. Beneath the spray of CGI blood and the sheen of oiled bodies lay a sophisticated, furious examination of power, human dignity, and the crushing weight of inevitable fate.

The visual language of *Spartacus* is unapologetically operatic. The showrunners, including creator Steven S. DeKnight and producer Sam Raimi, eschewed naturalism for a heightened, graphic novel aesthetic. The sky is always a little too golden or too stormy; the blood does not drip, it splashes across the lens in slow-motion crimson arcs. This artificiality, rather than detaching the viewer, creates a suffocating "hyper-reality" that mirrors the gladiators' existence. In the ludus (gladiator school), reality is performative. Life is cheap, but death is theatre. The camera traps us in this claustrophobic world alongside the slaves, making the wide, open shots of the eventual rebellion feel like a genuine gasp of oxygen.

At the heart of the series’ initial brilliance—and its enduring sorrow—is the performance of the late Andy Whitfield. As the titular Thracian in the first season, Whitfield brought a soulful, wounded gravity that grounded the show’s campier elements. He played Spartacus not merely as an action hero, but as a husband stripped of his humanity, fighting to reclaim his name. His eyes held a vulnerability that made the violence tragic rather than triumphant. The show’s production history is haunted by Whitfield’s real-life battle with non-Hodgkin lymphoma and his untimely death, forcing a recasting with Liam McIntyre for the subsequent seasons. While McIntyre performed admirably, carrying the torch of rebellion with a harder, battle-weary edge, Whitfield remains the show’s spiritual center—a ghost in the arena whose memory fueled the narrative’s emotional stakes.

Crucially, the series thrives on its villains as much as its heroes. John Hannah (Batiatus) and Lucy Lawless (Lucretia) deliver performances of Shakespearean villainy. They turn the "upstairs/downstairs" dynamic of the ludus into a snake pit of social climbing. They are not merely evil; they are desperate, petty, and striving, embodying the banality of evil where human lives are traded for social invitations and political favor. The scene in the Season 1 finale, "Kill Them All," where the slaves finally turn on their masters, is not just an action set piece—it is a cathartic, blood-soaked dismantling of a corrupt society, earned through thirteen episodes of humiliation and rage.

Ultimately, *Spartacus* transcends its "sword and sandal" genre trappings. It evolves from a story of personal vengeance into a broader commentary on the cost of freedom. It asks uncomfortable questions about what we are willing to sacrifice for liberty and whether a man can remain whole when his world is built on slaughter. It remains a unique artifact of television history: a show that lured audiences in with the promise of blood, only to break their hearts with the tragedy of the men and women forced to spill it.