✦ AI-generated review

The Utopia of the Ninety-Ninth

In the lineage of Michael Schur’s television universe—a canon defined by the sunny bureaucracy of *Parks and Recreation* and the philosophical optimism of *The Good Place*—*Brooklyn Nine-Nine* stands as the most complicated artifact. Premiering in 2013, it offered a seductive proposition: what if the instruments of state power were wielded not by cynics or brutes, but by a found family of lovable eccentrics? For eight seasons, the series operated as a kind of civic fantasy, positing a world where competence and kindness were the ultimate weapons against crime.

Visually, the series rejects the desaturated grit typical of the police procedural. The 99th precinct is bathed in high-key lighting and primary colors, a playground for the camera rather than a dungeon for suspects. The editing is rhythmic and snappy, utilizing the "zoom-in" crash often to punctuate a joke rather than to heighten tension. This aesthetic choice is crucial; it disarms the viewer, stripping the setting of its inherent menace. In this precinct, the interrogation room is less a site of coercion than a stage for the brilliant "bottle episode" theatrics of "The Box," where psychological chess replaces physical intimidation.

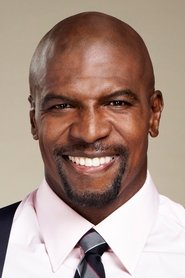

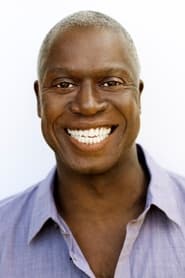

At the center of this optimistic experiment stands Captain Raymond Holt, portrayed with Shakespearean gravity by the late Andre Braugher. Holt is the show’s moral anchor and its most subversive creation. As a gay Black man who rose through the ranks of a prejudiced era, his stoicism is not merely a comedic device to contrast with Andy Samberg’s manic Jake Peralta; it is a survival mechanism honed over decades of exclusion. Braugher played Holt not as a robot, but as a man whose emotions ran so deep they required a fortress to contain them. His relationship with Peralta drives the show’s emotional engine: the slow, painstaking maturation of a reckless "action hero" archetype under the tutelage of a father figure who demands dignity over glory.

However, the show’s greatest conflict was never the "criminal of the week," but rather the friction between its gentle heart and the hardening reality of American policing. As the cultural conversation around law enforcement shifted following 2020, the show’s premise—that good cops can fix a broken system from the inside—began to buckle. To its credit, the series did not retreat into denial. The final season is a fascinating, if occasionally clumsy, act of self-interrogation. We watch the fantasy dissolve as characters like Rosa Diaz step away from the badge, unable to reconcile their morality with the institution. The visual brightness remains, but the air in the bullpen grows heavier, burdened by the realization that camaraderie alone cannot solve systemic fracture.

Ultimately, *Brooklyn Nine-Nine* succeeds not as a realistic depiction of police work, but as a humanist plea. It asks us to imagine a world where authority figures are defined by their vulnerability rather than their force. It is a show about detectives who investigate their own flaws as rigorously as they do their cases. While the "good cop" may be a myth in the gritty realism of modern discourse, inside the protective bubble of the 99th precinct, it was a beautiful, comforting dream that finally, and necessarily, had to wake up.