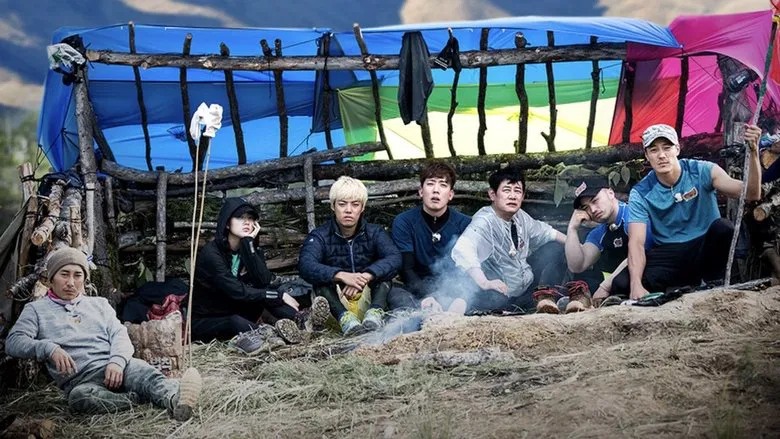

The Architecture of SurvivalIn 2011, the landscape of South Korean television was dominated by studio-polished variety shows and slick, urban melodramas. Into this sanitized ecosystem dropped *Law of the Jungle*, a program that didn't just ask celebrities to step out of their comfort zones, but violently relocated them to the bottom of the food chain. Directed by Kim Jun-su, this series (which functions narratively and visually like an episodic survival film) offered a stark counter-narrative to the K-pop industrial complex: what happens when you strip the idol of their stage, their stylist, and their script? The result is a fascinating, if occasionally dissonant, study of human fragility and the performative nature of "reality."

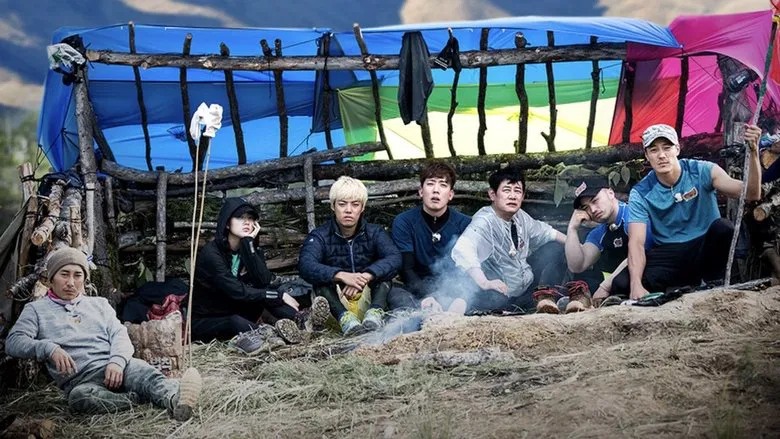

The visual language of *Law of the Jungle* is defined by a claustrophobic vastness. Unlike the controlled environments of western counterparts like *Survivor*, where the game mechanics are visible, Kim Jun-su’s lens focuses on the indifference of nature. The camera lingers on the blistering sun, the torrential unexpected downpours, and the oppressive density of the foliage.

There is a deliberate graininess to the cinematography—a shaky, handheld aesthetic that signals "authenticity" even when the editing room dictates the narrative flow. The framing often dwarfs the cast members against towering trees or endless oceans, visually reinforcing their insignificance. It creates a suffocating sense of reality where the enemy isn’t a voting council, but the basic caloric deficit of the human body.

At the center of this storm stands Kim Byung-man, the "Chieftain." To view his performance merely as a host duty is to misunderstand the show’s structural integrity. Kim is not playing a character; he is the anchor of competence in a sea of helplessness. The show’s emotional core relies entirely on the dynamic between his stoic capability and the desperate reliance of his "tribe." Watching a meticulously groomed pop star or a revered actor reduced to begging for a piece of roasted lizard offers a voyeuristic thrill, certainly. But the deeper resonance lies in the dismantling of the celebrity hierarchy. In the jungle, social capital is worthless; the only currency is the ability to start a fire or spear a fish.

However, the show is not without its epistemological problems. The "conversation" surrounding *Law of the Jungle* has always been haunted by the specter of fabrication—the tension between documentary truth and entertainment value. There are moments where the narrative collapses under its own ambition to be thrilling, where the "accidental" encounters with wildlife feel suspiciously curated. Yet, to fixate on whether every struggle is unscripted is to miss the point of the art form. The emotional truth—the exhaustion in the eyes, the genuine camaraderie forged in hunger, the terror of the dark—is real, even if the stage is managed.

Ultimately, *Law of the Jungle* succeeds because it exposes the modern human condition. We are comfortable, fed, and entertained, yet we yearn to see our proxies suffer and survive in the dirt. It is a vicarious return to the primitive, reminding us that beneath the veneer of civilization, we are all just one missed meal away from the wild. It is not a perfect documentary, but as a piece of cultural theater, it is undeniably compelling.