✦ AI-generated review

The Architecture of Regret

When it was announced that *Breaking Bad*’s comic-relief lawyer, Saul Goodman, would receive his own spinoff, the collective sigh of skepticism was audible. In the cynical calculus of modern television, this reeked of a network refusing to let a cash cow die, a desperate attempt to scrape the bottom of the "blue meth" barrel. Yet, what creators Vince Gilligan and Peter Gould delivered in *Better Call Saul* was not a footnote to a masterpiece, but a masterpiece in its own right—a tragedy so quiet, so methodical, and so devastatingly human that it arguably eclipses the show that birthed it.

If *Breaking Bad* was a frantic, adrenaline-fueled descent into chaos, *Better Call Saul* is a slow-motion car crash that lasts six seasons. We know the destination; the horror lies in watching the driver wrestle with the wheel.

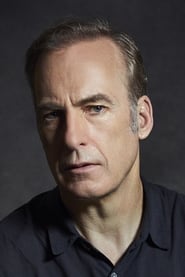

Visually, the series operates with a discipline rarely seen in the medium. The directors do not treat the camera as a recording device, but as a painter’s canvas. The cinematography is defined by its stillness and its negative space. A dropped ice cream cone on a sidewalk is framed with the gravity of a crime scene; a lawyer taping a light switch becomes a Sisyphean struggle. This visual language—often juxtaposing the sun-bleached emptiness of the New Mexico desert with the claustrophobic, shadow-drenched interiors of legal offices—mirror the internal landscape of Jimmy McGill (Bob Odenkirk). The show demands patience, training the viewer to find tension not in gunfire, but in the silence between two people in a room.

At its core, this is a story about the devastating weight of brotherhood and the insidious nature of identity. The central conflict is not between a lawyer and a cartel, but between Jimmy and his brother, Chuck (Michael McKean). Chuck is a man of the law, brilliant but paralyzed by a psychosomatic illness and a festering resentment for his charismatic, rule-breaking younger brother. The tragedy is that Chuck is technically right about Jimmy—he is dangerous with a law degree—but Chuck’s cruelty is the self-fulfilling prophecy that pushes Jimmy toward the abyss. It is a Cain and Abel story where Abel slowly poisons Cain with condescension.

However, the show’s beating heart—and its greatest surprise—is Kim Wexler (Rhea Seehorn). Kim is not merely a love interest or a moral compass; she is the most fascinating enigma in the Gilligan universe. Her relationship with Jimmy is the series' most tragic element. It is not a story of a good woman corrupted by a bad man, but of two broken people who discover that their broken pieces fit together to form a weapon. The scenes they share, particularly the quiet moments smoking cigarettes in the shadows of the HHM parking garage, are intimate and heavy with unspoken doom. We watch, helpless, as their love becomes the very vehicle of their destruction.

Bob Odenkirk’s performance is a high-wire act of pathos. He layers the sleazy charm of Saul Goodman over the desperate, eager-to-please vulnerability of Jimmy McGill. We see him trying, failing, and eventually deciding that if the world sees him as a monster, he might as well be the best monster in town.

In the end, *Better Call Saul* is a profound meditation on consequences. It refutes the glamorous anti-hero myth by showing us the mundane, gray aftermath of "breaking bad." It suggests that the true punishment for our sins is not death, but having to live with the person we have become. It is a show about the law that feels like a crime story, and a crime story that feels like a heartbreak.