The Seductive Architecture of EvilThe espionage genre often relies on the comfort of distance. We are accustomed to viewing spies as kinetic objects moving through interchangeable exotic locales, detached from the human cost of their trade. However, *The Night Manager* (2016), Susanne Bier’s sumptuous adaptation of John le Carré’s post-Cold War novel, refuses us that safety. It posits that the true horror of the modern world isn't found in the shadows, but in the blindingly bright sunlight of a Mediterranean villa, sipping champagne while the world burns. It is a miniseries that functions less like a procedural and more like a slow-motion car crash involving a Rolls Royce: devastating, expensive, and impossible to look away from.

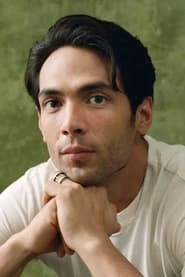

Bier, a director known for her intense domestic dramas, applies an uncomfortable intimacy to the sprawling geopolitical canvas. Her camera does not simply observe; it invades. In the opening sequences set during the Arab Spring in Cairo, the juxtaposition is visceral. We see the riotous, blood-stained streets through the hermetically sealed glass doors of the Nefertiti Hotel, where Jonathan Pine (Tom Hiddleston) presides as the titular night manager. The visual language here is striking: the "Night Manager" is a creature of service and silence, a man who has hollowed himself out to become the perfect vessel for others' secrets. Hiddleston’s performance is a masterclass in stillness; he is a coiled spring hidden beneath a bespoke suit, his eyes betraying a soldier’s trauma masked by hospitality.

The narrative engine is driven by the dynamic between Pine and Richard Roper (Hugh Laurie), a man described with chilling simplicity as "the worst man in the world." Laurie’s interpretation of Roper is a revelation. He eschews the mustache-twirling tropes of the Bond villain for the terrifying approachability of a CEO. Roper is charming, paternal, and educated; he treats the sale of napalm and nerve gas with the same casual discernment one might apply to a wine list. The show’s brilliance lies in how it seduces the audience just as Roper seduces Pine. We are lured in by the private jets, the Zermatt chalets, and the azure waters of Mallorca, forcing us to confront our own complicity in the glamour of violence. We want to be at Roper's table, even as we know what pays for the feast.

The adaptation makes a pivotal change from the source material by transforming the intelligence handler, Burr, into a woman, played with gritty resolve by Olivia Colman. This is not a superficial nod to diversity but a thematic necessity. Colman’s Angela Burr—pregnant, frumpy, and operating out of a grim London office—serves as the moral counterweight to Roper’s phallic displays of missile power. While Roper creates death from a distance, Burr is creating life. She grounds the narrative, reminding us that the "game" played by these men has tangible, bloody consequences. The scene where Roper demonstrates his weaponry in the desert, treating explosions like fireworks at a garden party, is the series' visual thesis: a terrifying conflation of beauty and atrocity.

Ultimately, *The Night Manager* is a story about performance. Pine is a spy playing a criminal; Roper is a monster playing a gentleman. By the time the curtain falls on this six-part morality play, the lines between the roles have blurred. It stands as a sophisticated critique of the West’s relationship with war—a dazzling, intoxicating nightmare that leaves us questioning not just the characters, but the very allure of the genre itself.