✦ AI-generated review

The Anvil of England

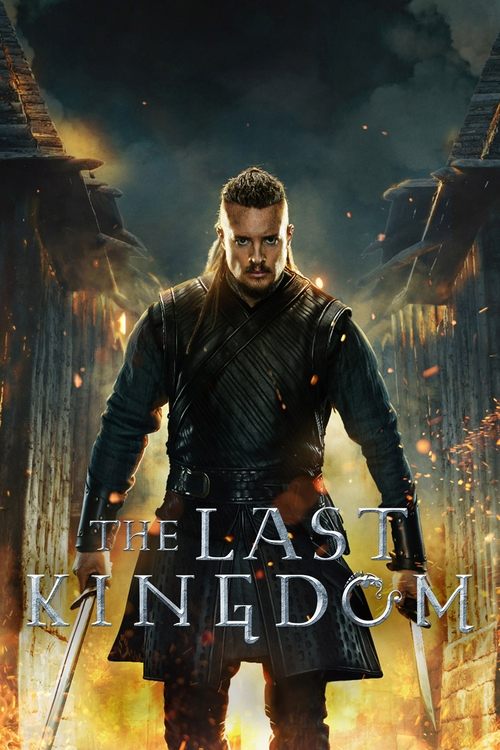

In the mid-2010s, television was colonized by dragons. As the cultural monolith of *Game of Thrones* cast a long, fantastical shadow over the medium, a quieter, grittier contender emerged from the BBC (and later Netflix) to stake its claim on the shield wall of historical drama. *The Last Kingdom*, adapted from Bernard Cornwell’s *The Saxon Stories*, initially appeared to be a modest cousin to HBO’s juggernaut—another show about men with swords and muddy furs. However, to dismiss it as a genre filler is to ignore one of the most intellectually satisfying and emotionally resonant explorations of nation-building ever put to screen. This is not a story about winning a throne; it is a story about the painful, messy invention of an idea called "England."

Unlike its fantasy counterparts, *The Last Kingdom* does not rely on magic or shock value. Its visual language is defined by the suffocating intimacy of the shield wall. The direction strips away the glamour of medieval combat, presenting it not as a ballet of choreography but as a claustrophobic crush of bodies, breath, and mud. The cinematography creates a tangible sense of place—you can practically smell the woodsmoke and feel the damp chill of the Wessex marshes. This grounding is essential, because the show’s true conflict is not on the battlefield, but in the soul of its protagonist, Uhtred of Bebbanburg (Alexander Dreymon).

Uhtred, born a Saxon noble but raised by Danish invaders, serves as the living embodiment of the cultural collision that formed Britain. Dreymon imbues the character with a charming, arrogant swagger that slowly matures into weary wisdom, but the show’s genius lies in his dynamic with King Alfred the Great, played with fragile intensity by David Dawson. This relationship is the series' beating heart. They are polar opposites: Uhtred is a pagan warrior who values instinct and reputation; Alfred is a pious, sickly intellectual who values law and legacy.

Their scenes together are electric, functioning as a dialectic on how history is made. In one of the series’ most poignant moments, Alfred—near death and stripped of his royal posturing—admits that his holy England was built on the back of Uhtred’s "pagan" sword. It is a rare admission in a genre that often deals in absolutes. The show posits that a nation cannot be formed solely by the ink of laws or the blood of warriors; it requires both the dreamer and the butcher, and they will rarely like each other.

While the narrative occasionally stumbles under the repetitive cycle of banishments and reconciliations—a byproduct of adapting Cornwell’s episodic novels—the thematic arc remains remarkably consistent. The series resists the urge to modernize the morality of its characters. The Danes are not misunderstood freedom fighters; they are brutal colonizers. The Saxons are not noble defenders; they are often religious zealots. The audience is forced to navigate this grey morality alongside Uhtred, whose mantra, "Destiny is all," evolves from a fatalistic shrug into a declaration of endurance.

Ultimately, *The Last Kingdom* succeeds because it treats history not as a backdrop for adventure, but as a tragedy of identity. It concludes (specifically in its fifth season finale, before the coda of the film *Seven Kings Must Die*) with a sense of completion that is rare in the streaming era. It leaves us with the understanding that the map of England was drawn not just by kings in castles, but by the outcasts who stood on the wall between two worlds, unloved by history books but essential to their writing.