✦ AI-generated review

The Scalpel and the Ledger

In the traditional medical procedural, the hospital is a sanctuary. Whether it is the frantic, heroic trenches of *ER* or the soapy, interpersonal playground of *Grey’s Anatomy*, the institution itself usually holds the moral high ground. The doctors may be flawed, but the building is sacred. *The Resident*, however, begins with a desecration. In its opening moments, we do not see a miraculous save, but a negligent homicide committed by the Chief of Surgery, Dr. Randolph Bell. A selfie is taken, a hand trembles, an artery is nicked, and a patient dies. The subsequent cover-up is not a frantic mistake but a calculated administrative decision. From this bloody inception, the series establishes its thesis: modern medicine is no longer about the Hippocratic Oath; it is about the bottom line.

To view *The Resident* simply as another entry in the crowded genre of hospital dramas is to miss its specific, cynical vibration. It is, at its heart, a piece of "medical noir." The directors utilize the visual language of the sterile corridor not to comfort, but to alienate. The lighting in Chastain Park Memorial is often harsh and clinical, exposing the glossy veneer of a system that has been hollowed out by bureaucracy. The camera lingers on the expensive machinery and the pristine glass of the executive suites, creating a visual hierarchy where the boardroom looms physically and metaphorically over the operating theater. The show argues that the greatest threat to a patient’s life is not bacteria or trauma, but the "upcoding" of a billing cycle.

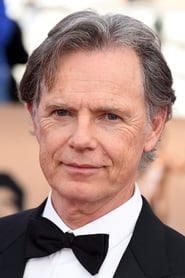

At the center of this systemic critique is the conflict between Dr. Conrad Hawkins and Dr. Randolph Bell, played respectively by Matt Czuchry and Bruce Greenwood. Czuchry, often cast for his sharp, frat-boy charm, here weaponizes that arrogance into a kind of guerrilla warfare. His Hawkins is less a doctor and more an insurgent, fighting behind enemy lines. He is the romanticized ideal of the "cowboy doctor," yet the show is smart enough to let us see the exhaustion in his eyes. He is Sisyphus with a stethoscope, pushing the boulder of patient care up a mountain of insurance paperwork.

However, it is Bruce Greenwood’s Dr. Bell who offers the show’s most compelling, if disturbing, gravity. In the first season, Bell is a terrifying creation: a "celebrity surgeon" whose skills have atrophied but whose ego—and value to the shareholders—remains intact. He is the personification of institutional rot. Watching Greenwood navigate the corridors with a predatory grace, hiding his trembling hand in his pocket, evokes a visceral dread that transcends typical melodrama. He represents the terrifying reality that in a for-profit system, a "bad" doctor who generates revenue is more protected than a "good" doctor who costs money.

The narrative often buckles under the weight of its own cynicism, occasionally drifting into hyperbolic villainy that feels more like a comic book than a hospital floor. Yet, these narrative excesses serve a purpose. They externalize the silent, invisible anxieties of the modern patient. When we watch a doctor check a watch during a code blue, or an administrator deny a scan to save a budget, *The Resident* is not just producing drama; it is validating the deep-seated public fear that we are merely assets to be managed until we depreciate.

Ultimately, *The Resident* functions as a grim mirror to the American healthcare industrial complex. It lacks the comforting warmth of its predecessors, refusing to offer the lie that "everything will be okay." Instead, it offers a sharper, colder truth: in the war between human life and fiscal solvency, the house always wins.