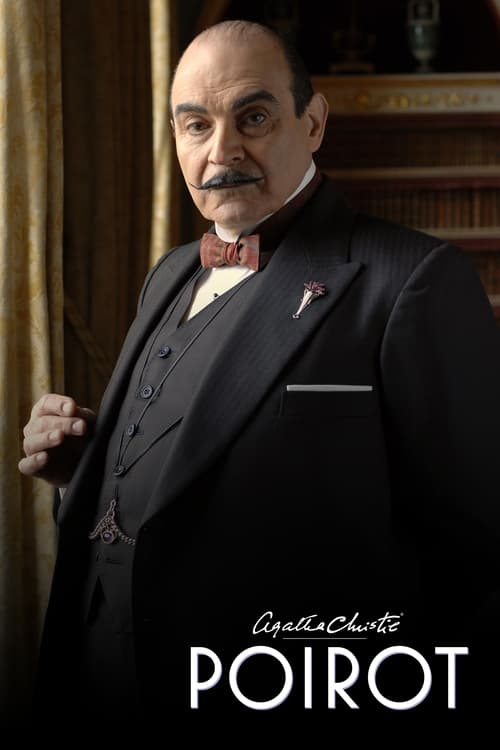

The Symmetry of the Soul: Reframing the DetectiveIn the vast, cluttered pantheon of literary detectives, most are defined by their chaos. Sherlock Holmes is a creature of erratic brilliance and chemical dependency; Philip Marlowe is a man stained by the grime of the city he navigates. Yet, in 1989, when David Suchet first minced onto the screen in *Agatha Christie’s Poirot*, he offered us a radical counter-proposition: that order, not chaos, is the ultimate instrument of justice. This monumental series, spanning nearly a quarter-century, is far more than a cozy collection of whodunits. It is a meticulous study of a man who believes that the restoration of balance to a broken world is a sacred, almost religious, duty.

To watch the early episodes of *Poirot* is to step into a perfectly preserved Art Deco dreamscape, a world of geometric lines and polished chrome that mirrors the detective's own internal architecture. The production design—often an unsung hero of the series—does not merely serve as period dressing; it acts as an externalization of Poirot’s psyche.

The visual language here is striking in its precision. The camera often lingers on the symmetry of a breakfast table or the perfect knot of a tie, suggesting that for this Belgian refugee, aesthetics and morality are inextricably linked. A crooked painting is an offense to the eye, just as a murder is an offense to the soul. Both must be straightened.

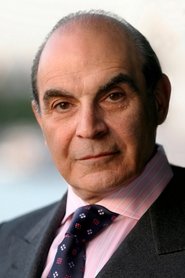

David Suchet’s performance is nothing short of a total inhabiting of a literary ghost. Unlike previous incarnations—the bombastic Albert Finney or the jovial Peter Ustinov—Suchet understood that Poirot is a tragic figure. He is a man trapped by his own genius, an outsider in the British upper class who is simultaneously revered and exoticized. Suchet plays him with a delicate melancholy. Beneath the fastidiousness, the mustache wax, and the comic vanity, there is a profound loneliness. He observes humanity with the keen, detached eye of a surgeon, understanding our passions and our greed without ever fully participating in them.

As the series matured, shedding the lighter, more caper-like tone of the 1930s short stories for the heavier, psychological weight of the later novels, the direction shifted accordingly. The sunny, sterile brightness of the early seasons gradually gave way to deeper shadows and a more somber palette. The adaptation of *Curtain: Poirot’s Last Case* stands as the harrowing emotional climax, transforming the charming sleuth into a fragile, dying man who must summon one final, terrible act of will. It is a testament to the show’s longevity that it allowed its protagonist to age, to weaken, and to confront the limitations of his own "little grey cells."

Ultimately, *Agatha Christie’s Poirot* endures not because of the puzzles, which are admittedly ingenious, but because of its philosophical core. In an era of television dominated by morally ambiguous anti-heroes and gritty realism, this series posits that civilization relies on the gentle, unwavering application of reason. Suchet gave us a Poirot who was fastidious not out of fussiness, but out of a desperate need to hold back the tide of human savagery. It is a performance, and a series, of enduring grace.