✦ AI-generated review

The Guillotine of the Nine-to-Five

If the modern workplace is a theater of performance—where we wear masks of "professionalism" to hide our messy, grieving, human selves—then *Severance* is not science fiction. It is a documentary of the soul. Created by Dan Erickson and directed with surgical precision by Ben Stiller and Aoife McArdle, this 2022 series arrived at a moment of supreme cultural fatigue. In the wake of a global pandemic that dissolved the boundaries between home and office, *Severance* offered a terrifying solution: what if you could surgically amputate the part of your brain that feels the drudgery of labor?

The brilliance of *Severance* lies in how it visualizes the corporate psyche. We are introduced to Lumon Industries, a retro-futuristic labyrinth that looks like mid-century modernism having a panic attack. The visual language here is suffocatingly precise. Stiller employs a lens of "retro minimalism"—low ceilings, endless white corridors, and a terrifying symmetry that traps the characters in the frame. The "Innies" (the work-only personas) inhabit a space that feels like a computer render of a purgatory, bathed in fluorescent greens and sterile whites. This is contrasted with the "Outie" world, which is shot in a wintry, melancholic dark blue. The aesthetic itself tells the story: the office is bright but dead; the world outside is dark but alive.

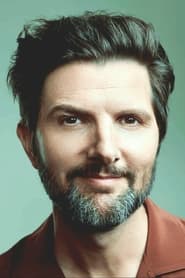

At the center of this bifurcated reality is Mark Scout, played by Adam Scott in a career-defining performance. Scott has always excelled at playing dry, reactive straight men, but here he performs a high-wire act of dissociation. He plays two distinct people who share a body. "Outie" Mark is a grieving widower, drinking himself into oblivion to numb the pain of his wife’s death. "Innie" Mark is a child of the corporation—eager, naive, and vaguely hollow. Scott’s genius is in the micro-expressions; the way his eyes shift from the heavy sorrow of the parking lot to the artificial brightness of the elevator is a masterclass in physical acting. He captures the tragedy of the premise: we sever ourselves not just to work, but to avoid feeling pain.

While the show offers the addictive pleasures of a mystery box—cryptic numbers, roomfuls of baby goats, and a waffle party that defies description—it avoids the trap of being *just* a puzzle. The narrative engine is powered by character, specifically the rebellion of Helly (Britt Lower). Her refusal to accept her enslavement serves as the audience’s proxy, screaming against the absurdity of a life lived entirely for a paycheck she will never see. The relationship between the Innies, particularly the tender, forbidden romance between Irving (John Turturro) and Burt (Christopher Walken), grounds the high-concept sci-fi in deep, aching humanity. It suggests that even in a brain-wiped vacuum, love and art will find a way to leak through the cracks.

*Severance* is more than a satire of corporate culture; it is an existential horror story about how we spend our time. It asks uncomfortable questions about consent and identity. If you cannot remember your work, are you really the one doing it? Or have you created a slave to carry your burdens? In a genre often obsessed with robots and aliens, *Severance* proves that the most terrifying alien landscape is the one we willingly walk into every Monday morning. It is a masterpiece of modern dread, arguing that the cost of a "perfect" work-life balance is nothing less than your soul.