The Architecture of DistrustCinema has long held a fascination with the "locked-room mystery," a narrative device that strips away the sprawling unpredictability of the open world and replaces it with a pressure cooker of human paranoia. It is a genre where geography dictates destiny, and where the walls are not just boundaries, but active participants in the drama. In *Safe House* (2025), director Jamie Marshall attempts to resurrect this claustrophobic tradition, blending the siege mechanics of *Assault on Precinct 13* with the paranoid finger-pointing of *The Thing*. While it occasionally stumbles over the furniture of its own genre tropes, the film succeeds as a muscular, kinetic exercise in spatial tension.

Marshall, a veteran of the industry with a deep pedigree in stunt coordination and second-unit direction (his fingerprints are on the gritty realism of *The Foreigner*), understands that action is not merely about movement, but about consequence. In *Safe House*, the violence is not a spectacle of CGI excess but a series of desperate, bone-crunching transactions. When the initial attack on a Vice Presidential motorcade forces six government agents into the titular bunker in downtown Los Angeles, the film shifts gears from a political thriller to a survival horror. The camera, operated with a nervous, handheld energy, prowls the grey, industrial corridors of the facility, emphasizing the suffocating reality that the danger is no longer just outside—it is sitting across the table.

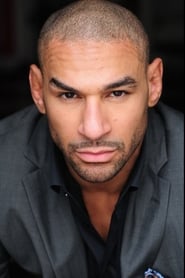

The script, penned by Leon Langford, navigates the familiar waters of the "mole hunt." We have the archetype of the stoic housekeeper, Anderson (Lucien Laviscount), and the martial prowess of Agent Choi (Lewis Tan), whose physicality is utilized to devastating effect in the film’s close-quarter skirmishes. However, the emotional anchor is Hannah John-Kamen’s Agent Owens. While the screenplay sometimes hands her exposition that feels more like a briefing document than dialogue, John-Kamen imbues Owens with a fragile lethality. She plays a woman haunted by PTSD, for whom the "safe house" is an oxymoron—no place is safe when your own mind is the battlefield. Her distrust is not just professional; it is pathological, which makes her the perfect lens through which to view the crumbling alliances.

Visually, the film excels when it stops talking and starts moving. Marshall’s direction transforms the bunker into a geometric puzzle of sightlines and blind spots. The lighting is harsh, utilitarian, casting long shadows that seem to hide the characters' true allegiances. When the inevitable breach occurs—mercenaries dropping through ceiling vents and shattering the illusion of security—the chaos is legible and impactful. Unlike the floaty, weightless battles of modern superhero fare, gravity applies here. Punches hurt, ammunition runs dry, and the environment degrades along with the characters' civility.

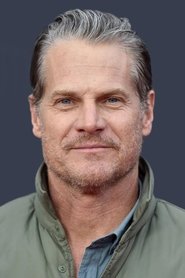

However, the film is not without its narrative structural weaknesses. The central mystery—which of the six agents is the traitor working for the "Copperheads" organization—unfolds with a rhythm that seasoned thriller fans might find slightly metronomic. The reveal of the antagonist, tied to the very top of the command chain, feels like a callback to the cynicism of 1970s political cinema, though it lacks the subversive bite of that era. The dialogue often serves the plot rather than the characters, leaving capable actors like Holt McCallany (channeling his grizzled *Mindhunter* energy) to do heavy lifting with thin material.

Yet, to dismiss *Safe House* for its adherence to formula is to miss the pleasure of its execution. It is a film that respects the "B-movie" ethos in the best possible way: it is efficient, unpretentious, and aggressively entertaining. It posits that in a surveillance state, the only privacy left is the secret you take to your grave.

Ultimately, *Safe House* stands as a testament to the enduring power of practical filmmaking. In an era of digital noise, there is something refreshingly analog about six people in a concrete box, waiting for the door to open. It doesn't reinvent the wheel, but it certainly knows how to spin it with dangerous velocity.