✦ AI-generated review

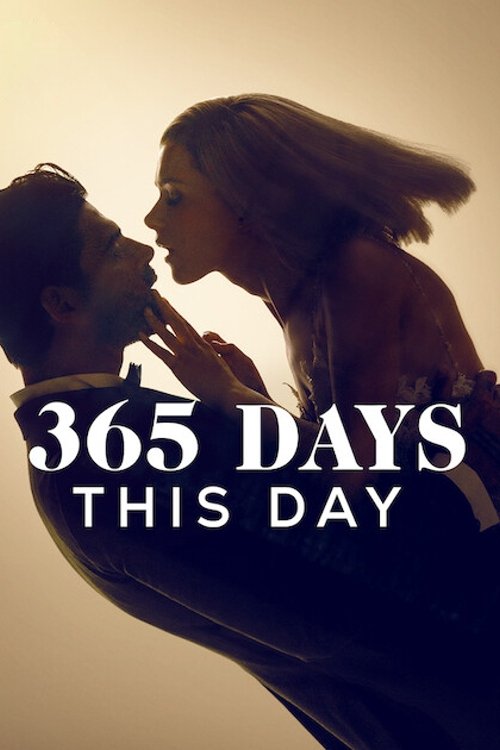

The Void in High Definition

Cinema, at its most elemental, is an empathy machine. It invites us to inhabit the skin of another, to feel the weight of their choices and the sting of their failures. However, *365 Days: This Day*, directed by Tomasz Mandes, offers a different proposition entirely. It does not ask for our empathy, nor does it request our suspension of disbelief. Instead, it demands a total suspension of thought, presenting a film that functions less as a narrative and more as a hypnotic, glossy screensaver for the id.

To criticize the film for its lack of plot would be to misunderstand its architecture. Mandes has constructed a film that is almost aggressively post-narrative. Where the first installment, controversial for its romanticization of captivity, at least possessed the crude momentum of a thriller, this sequel dissolves into a state of narrative inertia. We find Laura (Anna-Maria Sieklucka) and Massimo (Michele Morrone) married, yet their union is not explored through dialogue or dramatic friction, but through an endless parade of music video montages.

This is the film’s defining visual language: the montage. Cinematographer Bartek Cierlica shoots the Italian coastline and the actors’ bodies with the same sterile, hyper-saturated perfection found in luxury perfume commercials. Scene after scene—Massimo playing golf, Laura driving a Lamborghini, the couple having sex—is untethered from cause and effect. They are visual loops designed to be consumed in isolation. The film does not flow; it strobes. It creates a suffocating sense of reality where human connection is replaced by high-end consumerism. The characters do not speak to communicate; they speak only to bridge the gap between pop songs.

When the film attempts to introduce conflict, it retreats into the absurdities of soap opera logic. The introduction of Nacho (Simone Susinna), a rival gardener-turned-mobster, is meant to offer Laura an alternative to Massimo’s dominance. Yet, the film fails to grant Laura any true agency. She drifts from one possessive force to another, a beautiful object to be fought over rather than a human being with internal desires. The emotional core is hollow because the film refuses to engage with the trauma of her previous captivity, treating her psychological state as merely another costume change.

The climax, involving the reveal of Massimo’s evil twin brother, Adriano, is the moment the film abandons all pretense of grounding. It is a twist so camp and detached from human behavior that it renders the preceding drama instantly comedic. Yet, even here, Mandes directs with a straight face. There is no wink to the audience, no self-awareness that might have transformed this into a satire of excess.

Ultimately, *365 Days: This Day* is a fascinating cultural artifact not for what it says, but for what it lacks. It is a film stripped of the messy, uncomfortable textures of life—vulnerability, ugliness, difficult choices—leaving behind only a polished, empty shell. It reflects a viewer appetite for cinema that requires nothing, offering a frictionless slide into a fantasy where nothing matters, no one is real, and the music never stops.