The Art of the Blue-Collar MessFor the better part of the last decade, the landscape of the Black television sitcom was dominated by the "aspirational." Shows like *Black-ish* presented a polish of upper-middle-class success, where problems were often theoretical and the wardrobe was impeccable. *The Upshaws*, created by Regina Hicks and Wanda Sykes, rudely and delightfully shatters that glossy window. It is a throwback not just in format—the unfashionable multi-camera setup with a laugh track—but in spirit. It bypasses the Huxtables to shake hands with *Sanford and Son* and *Roseanne*, locating its heart in the messy, paycheck-to-paycheck reality of Indianapolis working-class life. It does not ask us to admire this family’s success; it asks us to witness their survival.

Visually, the series adheres to the rigid grammar of the classic sitcom: bright, flat lighting and a proscenium-style framing that turns the living room and Bennie’s garage into theatrical stages. In the hands of a lesser creative team, this would feel archaic. However, here, the visual language serves a specific purpose: it strips away cinematic pretension to focus entirely on the kinetic, almost vaudevillian energy of the performers. The camera doesn’t hide anything, mirroring the family’s inability to hide their own dirty laundry. The garage, cluttered and greasy, isn't just a set; it is a visual metaphor for Bennie Upshaw’s life—chaotic, held together by duct tape, but undeniably functional.

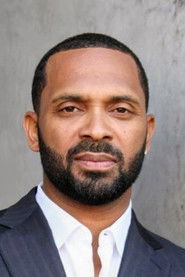

At the center of this storm is Bennie (Mike Epps), a character who defies the modern demand for "unproblematic" protagonists. Bennie is a mechanic, a hustler, and, by his own admission, a screw-up. The show’s central wound is not a sitcom misunderstanding that can be solved in twenty minutes, but a permanent scar: Bennie fathered a child with another woman during a "break" in his marriage to Regina (Kim Fields). This narrative choice is risky. It creates a tension that hangs over every laugh, grounding the slapstick in genuine pain. The presence of Kelvin, the "outside child," and his acceptance into the family unit, offers a complex look at blended families that few dramas, let alone comedies, dare to touch.

The friction that powers the show, however, is the antagonism between Bennie and his sister-in-law, Lucretia, played with razor-sharp precision by Wanda Sykes. This is the "bickering in-laws" trope raised to the level of bloodsport. Sykes, often sitting immobile on the couch like a sardonic queen on her throne, uses silence as effectively as her dialogue. Her disdain for Bennie is the audience’s proxy for judgment, yet the writing smartly evolves their relationship from pure hatred to a begrudging, trenches-style camaraderie. They are two people who would never choose each other, bound together by their mutual love for Regina.

Speaking of Regina, Kim Fields provides the necessary gravity to keep the series from floating away into caricature. She plays the "straight man" role with a weary resilience that feels incredibly lived-in. When she looks at Bennie, you see decades of history—exhaustion mixed with an stubborn, illogical affection.

Ultimately, *The Upshaws* succeeds because it refuses to sanitize the struggle. It finds humor in the uncomfortable spaces of financial insecurity and marital infidelity without mocking the characters experiencing them. It suggests that a "happy family" isn't one that avoids tragedy, but one that possesses the grit to endure it. In an era of curated online perfection, Bennie Upshaw’s unapologetic messiness feels like a radical, and necessary, act of honesty.