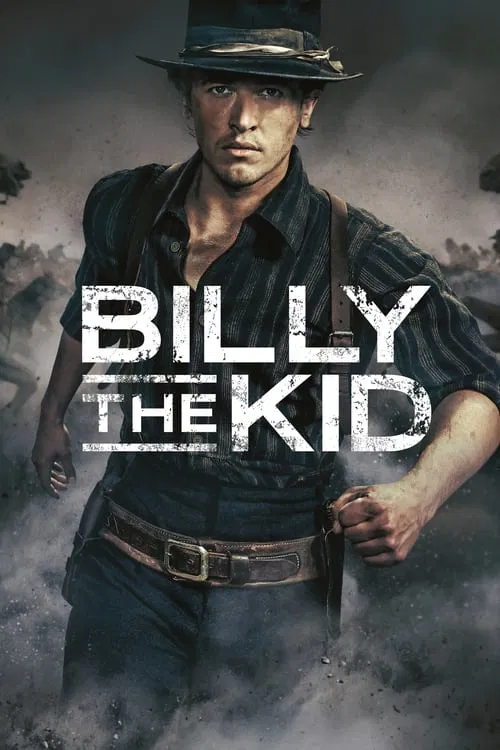

The Myth of the Gentle GunmanIn the vast, dusty lexicon of the American West, few names carry as much leaden weight as William H. Bonney. Yet, in Michael Hirst’s 2022 reimagining, *Billy the Kid* (MGM+), the weight we feel is not from the iron on his hip, but from the crushing silence of a soul misplaced in a violent world. Hirst, the architect behind *Vikings* and *The Tudors*, has long been a specialist in excavating the human from the historical effigy. Here, he turns his gaze to the Lincoln County War, offering not a revisionist history, but a melancholy ballad about an Irish immigrant boy who wanted a home and found only a battlefield.

Visually, the series rejects the sun-bleached sepia that often defines the genre. The cinematography favors a cooler, almost bruised palette—greys, deep blues, and the muddy browns of a frontier that feels wet, cold, and uninviting. This is not the mythic West of John Ford, where the horizon promises freedom; it is a claustrophobic landscape where the sky presses down on the characters. Hirst and his directors use wide shots not to show majesty, but isolation. When Tom Blyth (as Billy) rides across the plains, he looks small, a temporary mark on a land that is indifferent to his survival. The sound design mirrors this isolation; the howling wind often drowns out dialogue, emphasizing that in this version of the West, words are cheap, and connection is fleeting.

The emotional anchor of the series is Tom Blyth’s internal, almost fragile performance. He eschews the brash, laughing killer archetype popularized by Emilio Estevez in *Young Guns*. Instead, Blyth plays Billy as a creature of profound stillness. He is a boy forced into the shape of a man, his violence a reactive flinch rather than an aggressive posture. The chemistry between Billy and Jesse Evans (Daniel Webber) provides the narrative’s tragic spine. Their relationship is less a rivalry and more a doomed brotherhood, two orphans of the frontier clinging to opposite philosophies of survival.

Central to the series is the concept of the "sinner" versus the "outlaw." Hirst seems fascinated by the idea that Billy’s criminality was a bureaucratic invention—a label slapped onto a young man by the corrupt Santa Fe Ring to protect their own interests. The narrative meticulously deconstructs the Lincoln County War, transforming it from a simple shootout into a complex class struggle. We see the mechanisms of power—the handshake deals in smoke-filled rooms—that force men like Billy to pick up a gun. The tragedy isn't that Billy kills; it's that the civilization encroaching on the frontier is far more savage than the wilderness it seeks to tame.

Ultimately, *Billy the Kid* is a somber meditation on the inevitability of violence in the American story. It strips away the dime-novel glamour to reveal the lonely, terrified children beneath the cowboy hats. While it occasionally suffers from pacing issues common to streaming era bio-pics, struggling to stretch a short life into an episodic saga, it succeeds in its primary mission. It makes us mourn the boy before we judge the gunman. In a genre often obsessed with how men die, Hirst asks us to look, unflinchingly, at how they were never allowed to truly live.