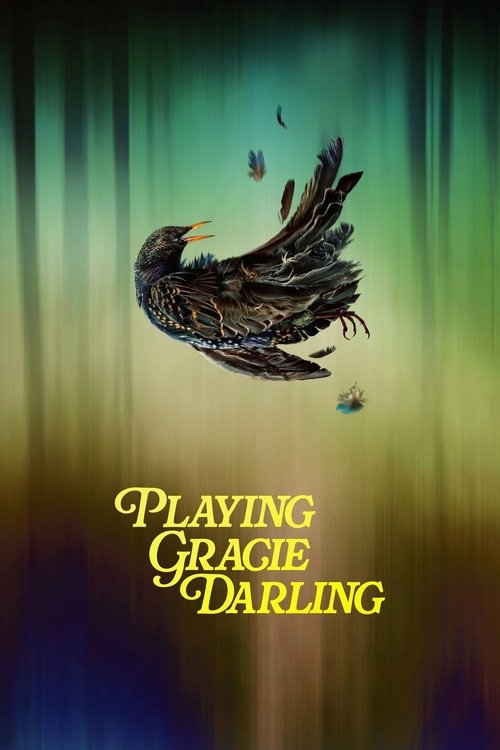

The Echoes of the UnburiedThere is a particular texture to Australian gothic—a sun-bleached dread where the vastness of the landscape serves not to liberate, but to entrap. In *Playing Gracie Darling*, director Jonathan Brough and creator Miranda Nation tap into this specific anxiety, crafting a narrative that is less about a missing girl and more about the residue she leaves behind. This is not merely a procedural about a cold case; it is a meditation on the way trauma, when left to ferment in the heat of a small town, curdles into myth.

Visually, Brough abandons the crisp, clinical look of modern crime dramas for something far more stifling. The town of Dorseth Bay is shot with a hazy, almost feverish quality, blurring the lines between the tangible and the imagined. The camera lingers on the frayed edges of the environment—the rust on a ute, the peeling paint of the local hall, the oppressive density of the surrounding bushland. This aesthetic choice is crucial; it suggests that the setting itself is a conspirator in the silence. The sound design complements this, utilizing a low-level hum of cicadas and wind that occasionally swells into a discordant roar, mirroring the internal noise of the protagonist, Joni.

At the narrative's center is the interplay of dual timelines, a structure often abused in the genre but here deployed with surgical precision to show the atrophy of hope. We witness the 1997 disappearance of Gracie Darling during a teenage séance—a scene crackling with adolescent energy and naivety—juxtaposed against the present-day disappearance of her niece. The transition between these eras is not jarring but fluid, suggesting that for the town's residents, the past isn't a foreign country; it's a room they never left.

The series is anchored by a ferocious, internal performance from Morgana O’Reilly as Joni. O’Reilly resists the urge to play the "returning investigator" trope with stoic detachment. Instead, her Joni is a raw nerve, a child psychologist whose professional armor disintegrates the moment she steps back into her hometown. Her skepticism regarding the supernatural elements—the "game" the local kids play to summon Gracie—is not just intellectual; it is a desperate emotional defense mechanism. If ghosts are real, then her guilt is eternal. If they are not, then the evil is human, which is infinitely worse.

Ultimately, *Playing Gracie Darling* transcends its "whodunit" framework to indict the patriarchal structures that demand female silence. The revelation of what truly happened in that shack—and the subsequent cover-up—exposes a community willing to sacrifice its daughters to protect its fathers. The supernatural elements, initially presented as the primary threat, reveal themselves to be manifestations of collective repression. The "ghost" is not a spirit seeking vengeance, but a memory demanding acknowledgement.

In a landscape saturated with true-crime reenactments and sterile mysteries, this series stands apart by refusing to offer clean closure. The final moments do not reset the status quo; they leave the characters standing in the wreckage of the truth, forever altered. It is a haunting reminder that while we may finish the game, we never truly stop playing it.