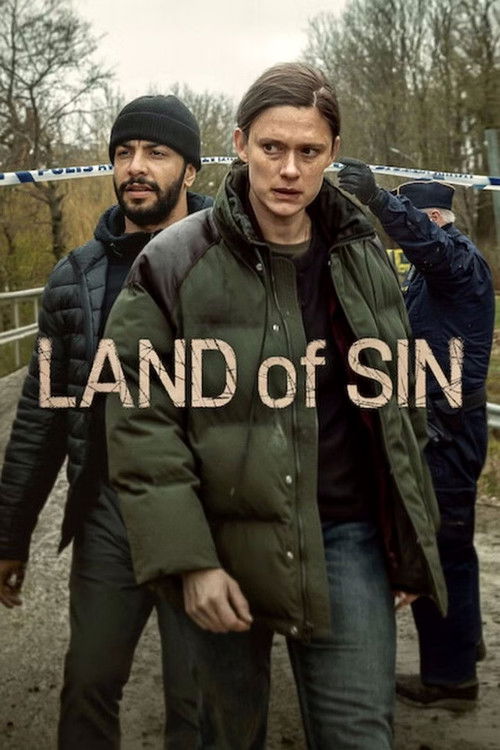

The Geology of GuiltThere is a particular texture to the silence in Peter Grönlund’s *Land of Sin* (originally *Synden*) that feels less like the absence of sound and more like a held breath. Nordic Noir has long traded on the currency of frozen wastelands and stoic detectives, a genre often in danger of becoming a parody of its own bleakness. But Grönlund, whose previous works *Goliath* and *Beartown* demonstrated a forensic interest in social margins, is not interested here in merely chilling our bones. He wants to break them. This five-part limited series is a brutal, mesmerizing excavation of a community where blood is not just thicker than water—it is the only currency that matters.

The series is set on the Bjäre peninsula, a landscape that Grönlund shoots not as a scenic backdrop but as a co-conspirator. The cinematography eschews the glossy, high-contrast crispness of typical Netflix crime procedurals for something muddier, grainier. The Scanian countryside here is oppressive, a "patriarchal rat-hole" of flat horizons and failing farms where the murder of a teenager, Silas, feels less like an anomaly and more like an inevitability.

The visual language mirrors the internal state of Dani, played with feral intensity by Krista Kosonen. Kosonen, known to international audiences from *Beforeigners*, undergoes a transformation here that is nothing short of physical. As the "perpetually angry" investigator with personal ties to the victim, she moves through the frame like a exposed nerve. Grönlund often frames her in tight, suffocating close-ups, allowing us to see the micro-tremors of a woman holding herself together by sheer force of will.

The friction between Dani and her new partner, Malik (Mohammed Nour Oklah), avoids the tired "buddy cop" tropes. Malik is the audience surrogate, the outsider trying to apply logic to a world governed by archaic feuds, while Dani operates on instinct and trauma. Their investigation into the death of Silas peels back the layers of a generational war, centered on the terrifying patriarch Elis (Peter Gantman).

What elevates *Land of Sin* above standard genre fare is its refusal to offer catharsis through procedure. The "whodunit" aspect is secondary to the "why." The scene where Dani confronts Elis is a masterclass in tension, not because of guns or shouting, but because of the terrifying silence of a man who believes his authority supersedes the law. Grönlund directs these moments with a heavy hand, emphasizing the weight of history that presses down on every character. The violence, when it comes, is not stylized action; it is desperate, messy, and pathetic.

Ultimately, *Land of Sin* is a tragedy about inheritance. It asks whether we can ever truly escape the sins of our fathers, or if we are doomed to re-enact their traumas on a loop. It is a difficult, demanding watch that offers no easy answers, cementing Grönlund’s reputation as one of the most vital social realists working in Scandinavia today. It does not just show us the darkness; it forces us to sit in it until our eyes adjust.