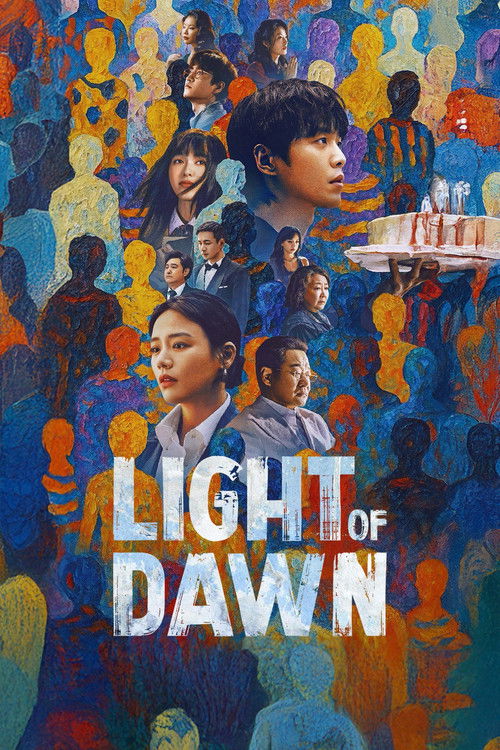

The Geometry of BloodIn the sprawling landscape of modern Chinese television, director Li Lu has carved a niche as a chronicler of the macro—helming massive, socially conscious epics like *In the Name of People* and *A Lifelong Journey*. With *Light of Dawn* (2025), however, he contracts his scope to the intimate, suffocating confines of a noir thriller, yet loses none of his sociological sharpness. Adapted from the novel *Blood Relativity*, this 18-episode limited series is less a "whodunit" and more a "whydunit," exploring how the sins of a previous generation calcify into the trauma of the next. It is a work that argues, with chilling precision, that the past is not a ghost—it is a bill collector that always comes calling.

Li Lu’s visual language here is a stark departure from the warm, nostalgic hues of his previous period pieces. Binchuan City is rendered in a palette of slate greys and sickly neon, a place where prosperity feels fragile and temporary. The series opens with a visual metaphor that is both absurd and terrifying: a human skeleton discovered inside a panda statue in Fangda Square. This image—the rotting core hidden within a symbol of commodified innocence—anchors the show’s aesthetic. The camera lingers on the cracks in the city's veneer, suggesting that the gleaming skyscrapers of the Wu family enterprise are built on foundations of bone. The "light" in the title is not hopeful; it is the harsh, interrogating glare of an operating room, exposing wounds that have been left to fester for twenty years.

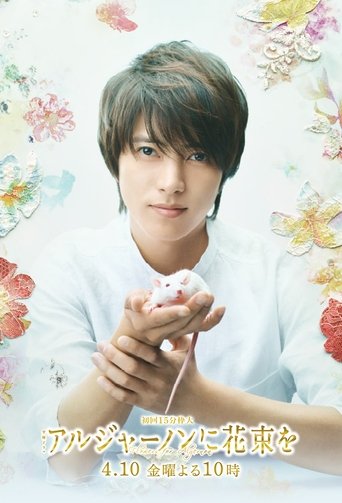

The narrative architecture rests entirely on the dual performances of Zhang Ruoyun as Gao Feng and Ma Sichun as Wu Feifei. Zhang, an actor known for his cerebral intensity in *Joy of Life*, here strips away all charisma to play a raw nerve of a man. As an orphan obsessed with his origins, he moves through the frame with a jagged, frantic energy, contrasting sharply with Ma Sichun’s portrayal of the heiress Wu Feifei. Ma plays Feifei not as a spoiled princess, but as a woman suffocating under the weight of her inheritance. When their paths converge—one seeking to dig up the truth, the other desperate to bury it—the screen crackles with the friction of their opposing needs. It is a testament to the direction that their relationship evolves not into a trite romance, but into a "complicity of survival," recognizing that they are both victims of the same original sin.

The series does falter slightly in its mid-section, a common ailment of the 18-episode format, where the procedural elements of the police investigation occasionally drag the pacing down. However, the script recovers by constantly returning to its central thematic thesis: the cruelty of biology. The show posits a brutal question about "blood relativity"—is family defined by the people who raise you, or the genetic code that damns you? The revelation of the skeleton’s identity forces Gao Feng to confront the possibility that his search for belonging was actually a march toward his own destruction.

Ultimately, *Light of Dawn* stands as a grim but sophisticated entry in the maturing genre of Chinese suspense noir. It eschews the sensationalism of cheaper thrillers for a melancholic look at the cost of justice. Li Lu proves that he does not need a cast of hundreds or a fifty-year timeline to tell a story about the state of the nation; sometimes, he only needs two broken children standing over a pile of bones, waiting for the sun to rise.